Understanding Request Latency with Profiling

It can be hard to figure out why response times are high in Java applications. In my experience, people either apply a process of elimination to a set of recent commits, or might sometimes use profiles of the system to explain changes in metrics. Making guesses about recent commits can be frustrating for a number of reasons, but mostly because even if you pinpoint the causal change, you still might not know why it was a bad change and are left in limbo. In theory, using a profiler makes root cause analysis a part of the triage process, so adopting continuous profiling should make this whole process easier, but using profilers can be frustrating because you’re using the wrong type of profile for analysis. Lots of profiling data focuses on CPU time, but the cause of your latency problem may be related to time spent off CPU instead. This post is about Datadog’s Java wallclock profiler, which I worked on last year, and explores how to improve request latency without making any code changes, or even seeing the code for that matter.

This is a personal blog and everything written below is my own personal opinion.

From metrics to profiles

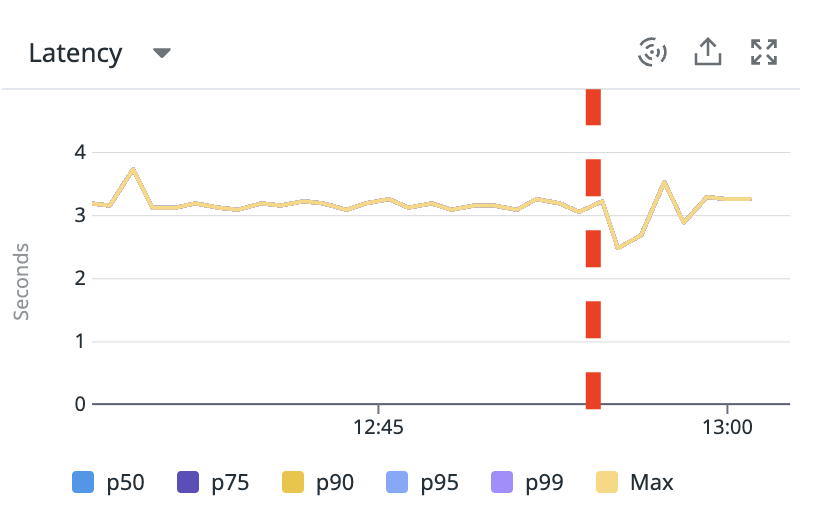

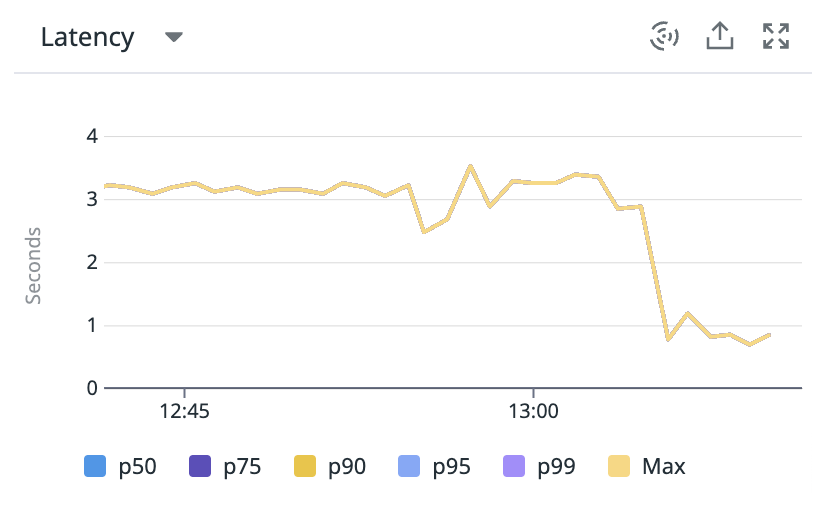

Suppose you have metrics which show you that request latency is too high for a particular endpoint.

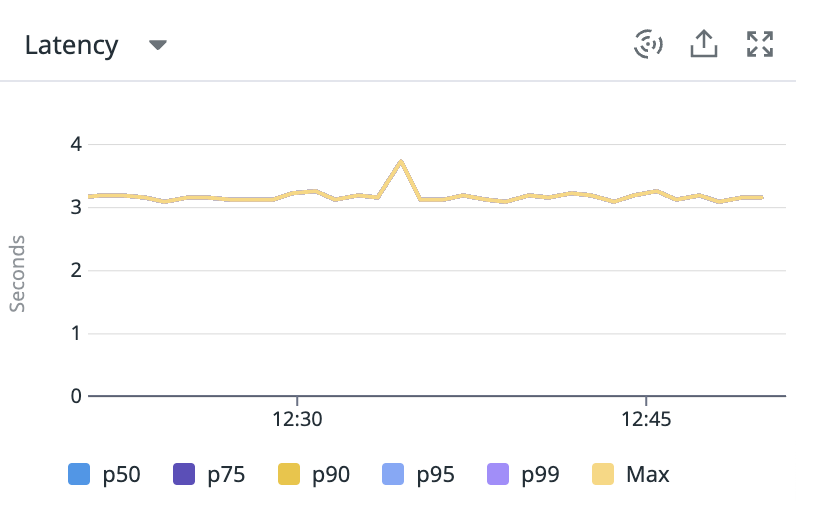

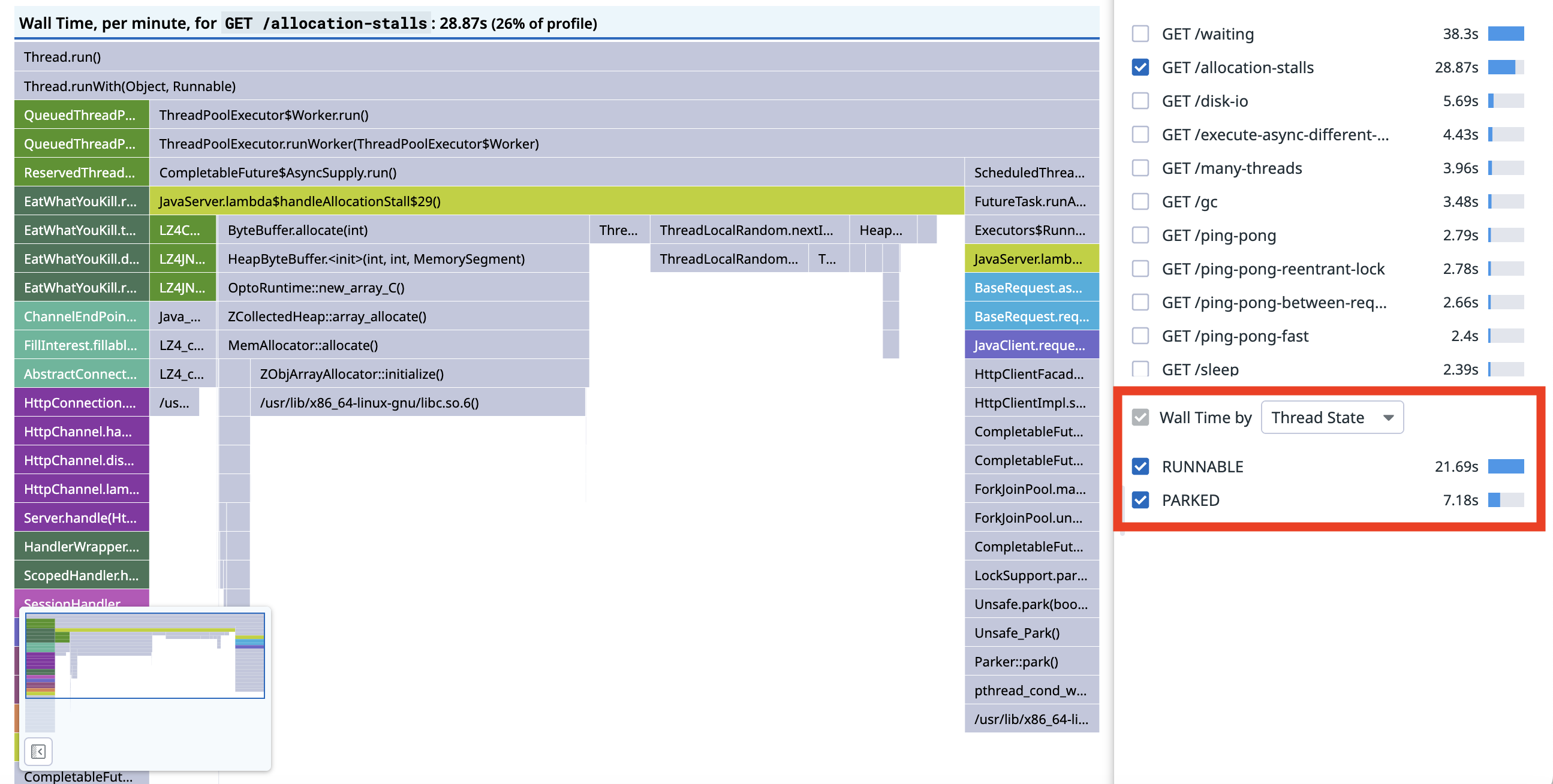

Here is the endpoint level latency timeseries for a slow endpoint GET /allocation-stalls (the name may create a sense of foreboding) in a very contrived demo Java application.

The response time is about 3-4s, which we would like to improve somehow without undertaking an R&D project.

Unless you have detailed tracing, you might start looking at profiles to do this.

OpenJDK has a built-in profiler called Java Flight Recorder (JFR), which Datadog has used historically for collecting CPU profiles from Java services.

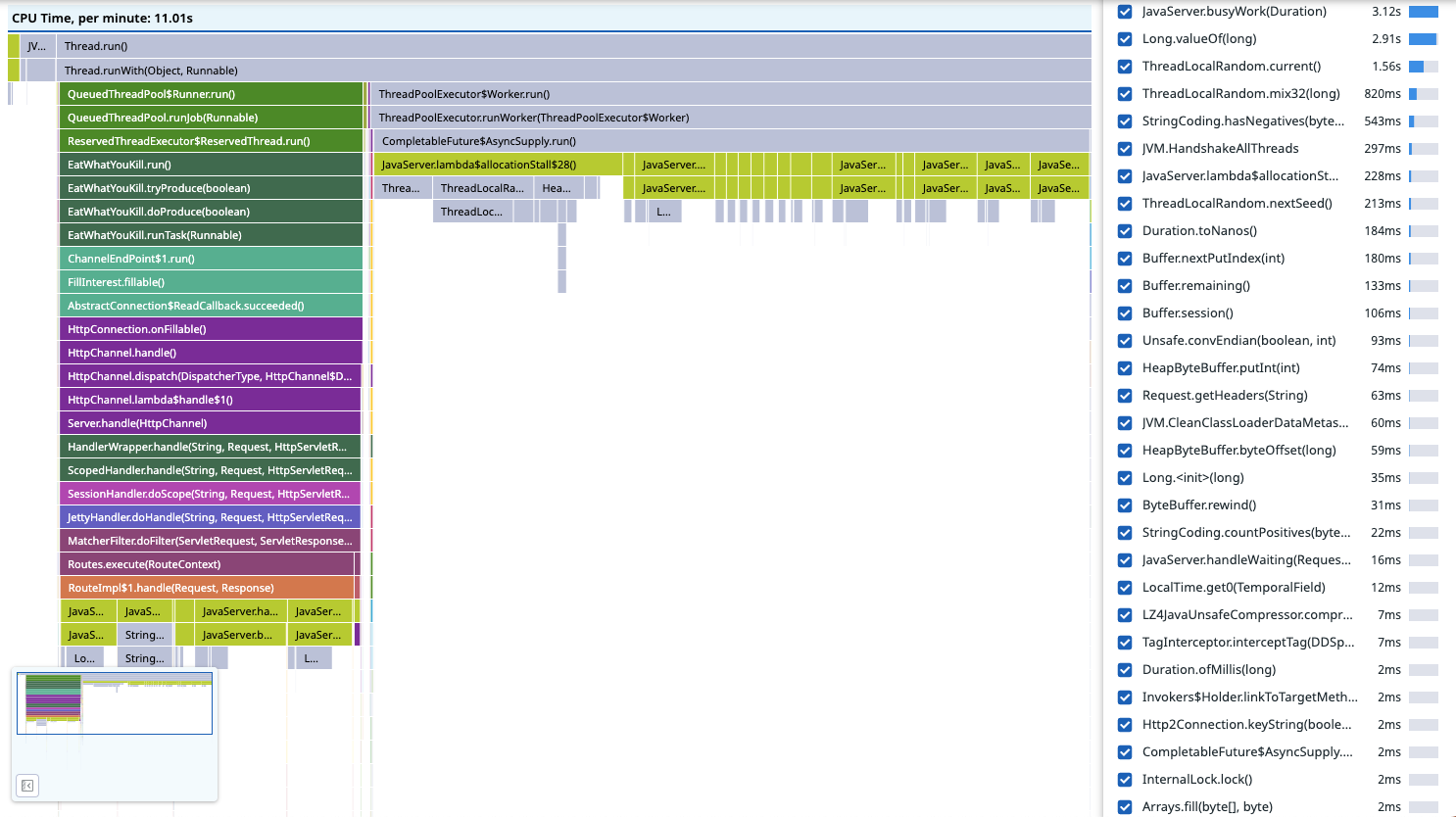

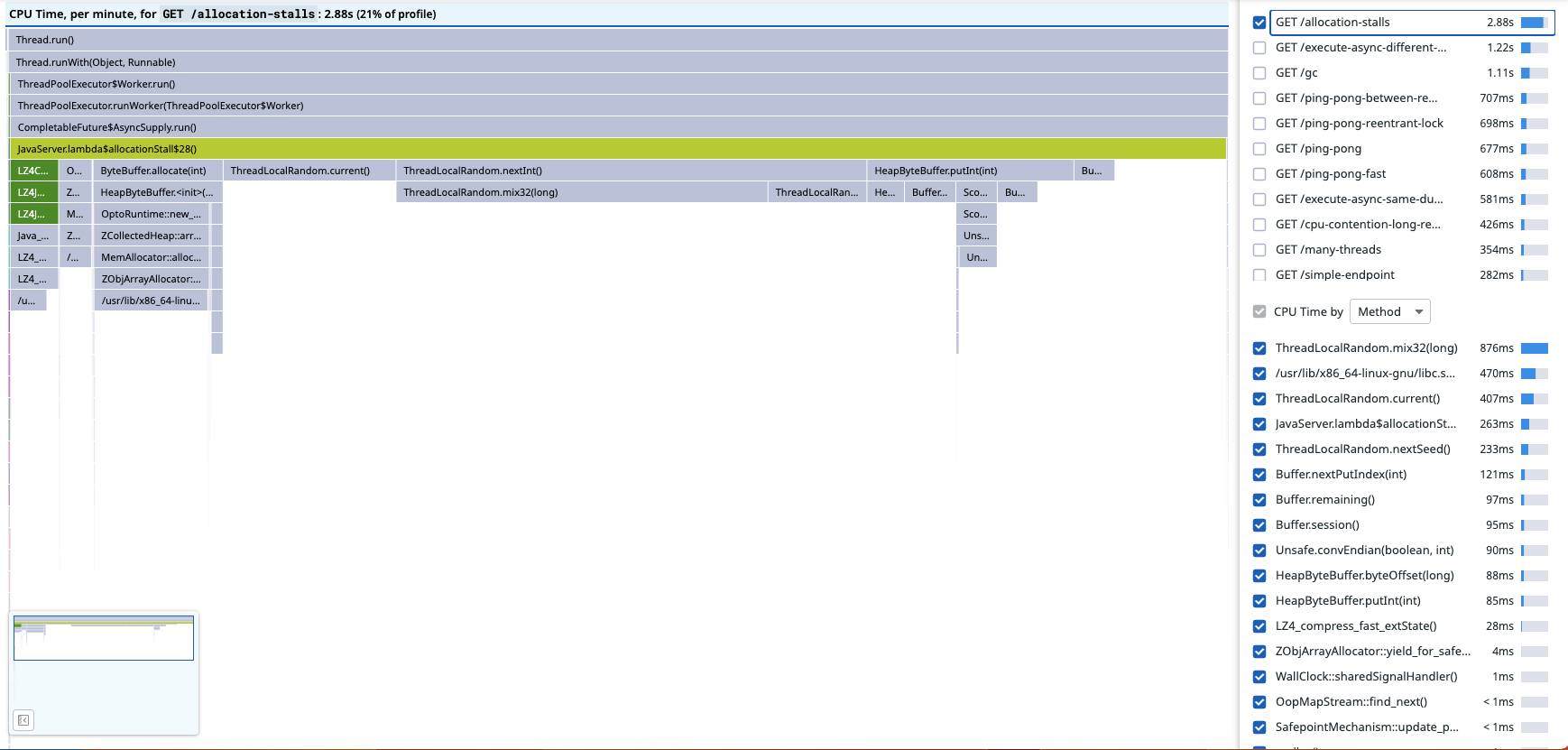

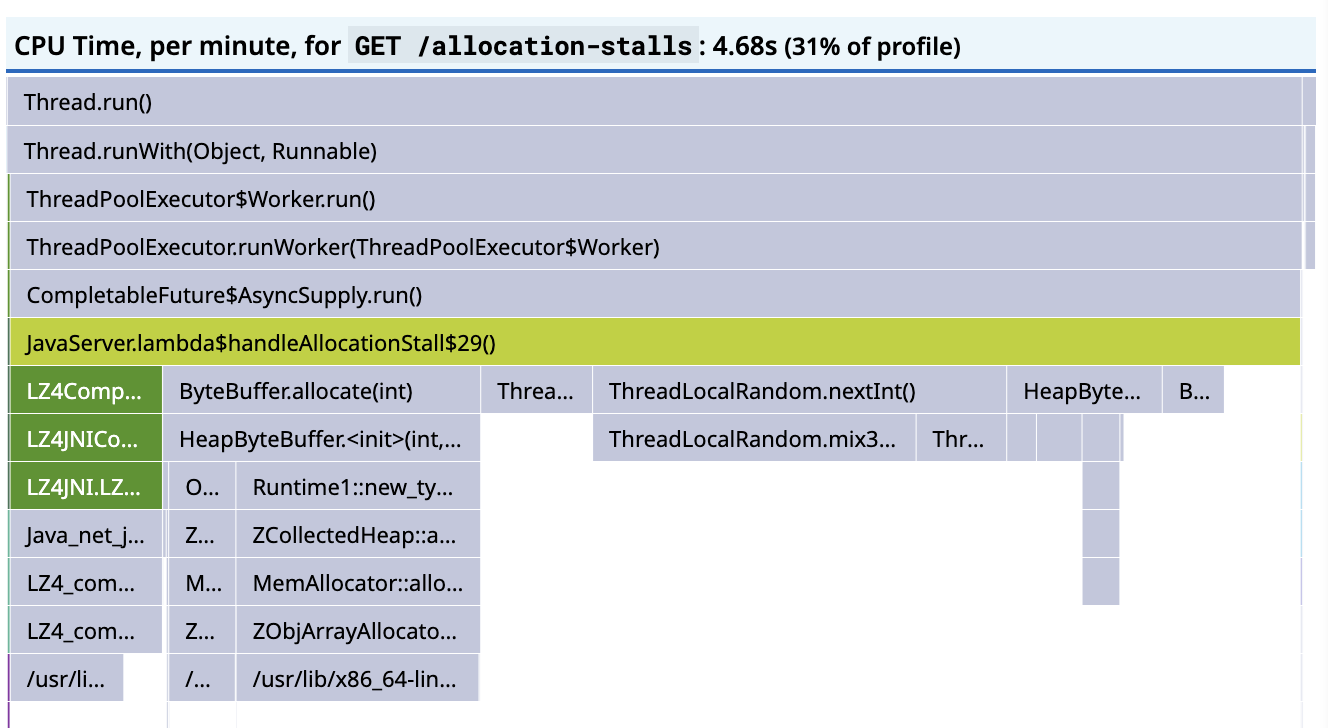

Here’s what a flamegraph of JFR’s jdk.ExecutionSample events looks like after being processed by Datadog’s profiling backend:

To the far left there is some JVM activity derived from JFR’s GC events.

Next to that there are some stack traces for Jetty’s routing (see JettyHandler.doHandle()).

To the right are stack traces for handling the requests in another thread pool (see ThreadPoolExecutor$Worker.run()).

There’s not much context beyond the frame names, and the most we have to go on is JavaServer.lambda$allocationStall$28() which we can probably guess is related to handling GET /allocation-stalls requests by its name.

Java code can be very generic and it’s not always straightforward to map frames to context by frame names alone, though in this case it’s easy enough.

Expanding it gets us to where I think most people turn away from profiling, assuming it was as easy to find the relevant frame as in this contrived example:

This points to random number generation being the bottleneck, which you aren’t likely to speed up. You may be able to reduce the number of random numbers generated, but in this contrived example, this would require renegotiating requirements. Part of the problem is that this flamegraph doesn’t show the complete picture. Without having the full picture, we can’t be sure we know what the bottleneck is, and might just be looking at the frame we happen to measure the most. This is where async-profiler comes in.

async-profiler

Some time ago, Datadog started experimenting with using async-profiler instead of JFR’s execution sampler in its continuous profiling product. There were two primary motivations for doing this:

- It’s better

- async-profiler has a much better CPU profiler than JFR, primarily because it can use CPU time (or other perf events) to schedule samples, whereas JFR uses wall time and a state filter.

- async-profiler has several approaches to unwinding native parts of the stack, whereas JFR does not unwind stacks with native frames.

- async-profiler reports failed samples so even if it’s not possible to get a full stack trace, it doesn’t distort the weights of other samples.

- We could modify the source code in a fork

- It’s easy to make changes to the source code and get those changes shipped in a timely manner.

- JFR doesn’t allow any contextualisation of samples, which makes presenting the data it reports in useful and engaging ways challenging. It was quite easy to extend async-profiler to support arbitrary, multi-dimensional labeling, whereas the process to get this functionality into JFR would be long-winded.

So async-profiler’s excellent codebase gave us a starting point for implementing some of the features we had in mind.

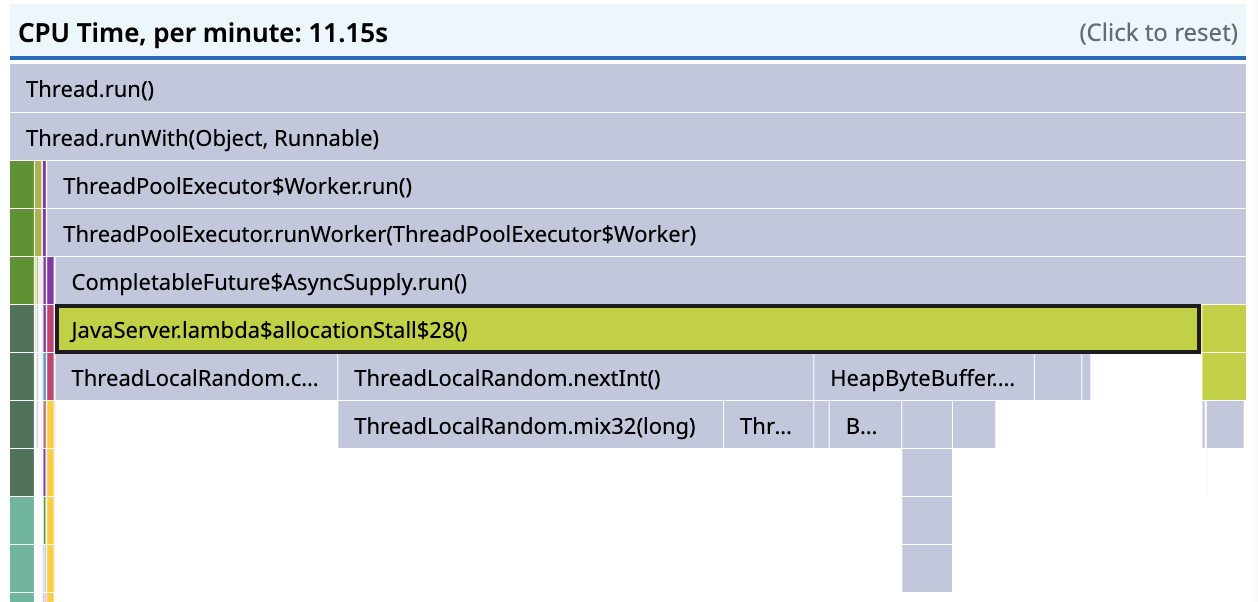

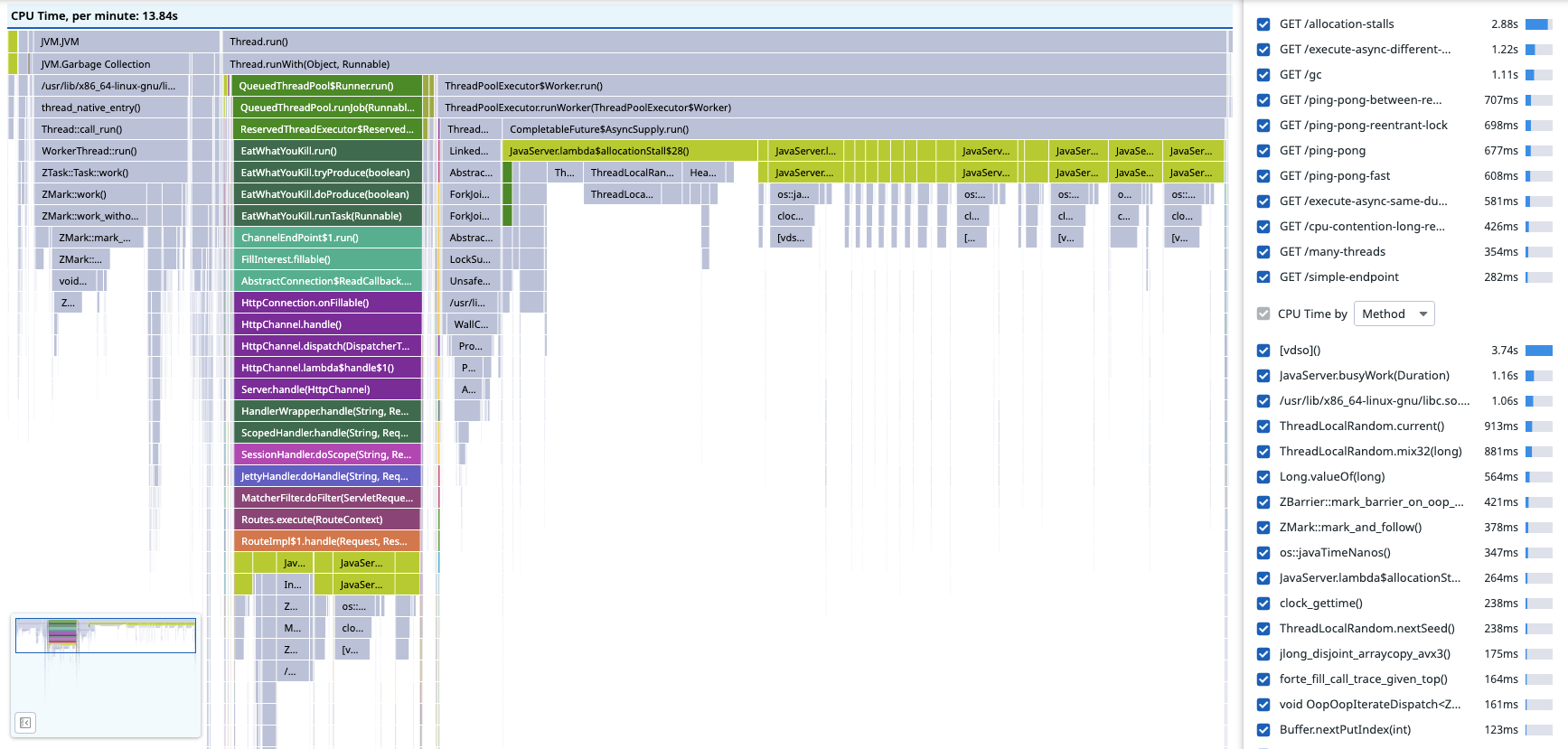

Below is a flamegraph of the same application as above recorded with Datadog’s customisation of async-profiler. Notice the ZGC activity to the left and compare it to the GC activity we could infer from JFR above, there’s more detail and it’s more obvious that the service has a GC problem.

Having access to the source code made it possible to add new fields to event types, such as correlation identifiers. Decorating samples with span ids makes it possible to link each sample to the endpoint being served, rather than guess based on the frame name (which only gets harder outside of contrived examples). This makes it possible to filter the flamegraph by endpoint instead of guessing based on the frame names:

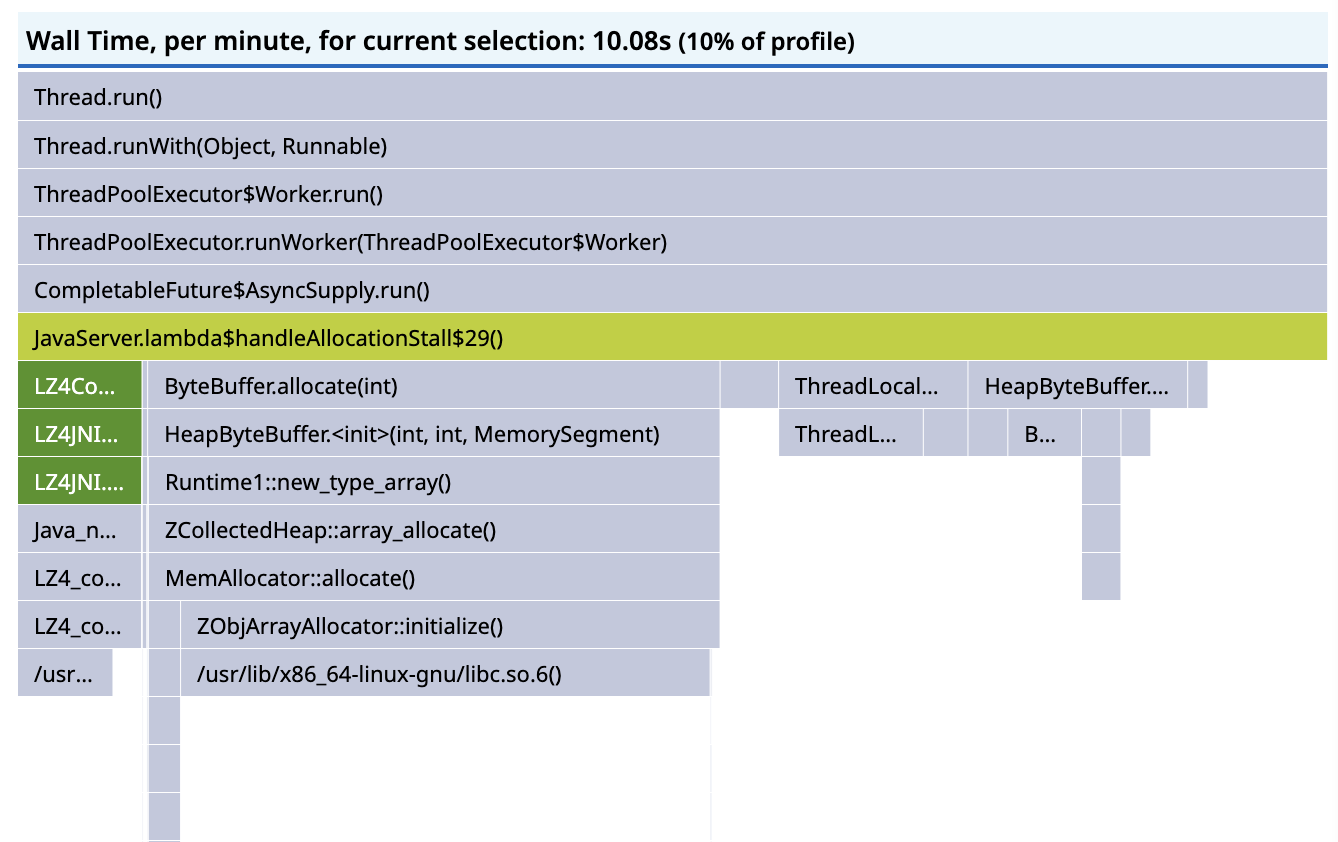

The green frames to the left, which are JNI calls into the lz4-java library, are missing from the JFR flamegraph because JFR won’t unwind stacks when the JVM is executing native code. In this particular case, this doesn’t actually distort the flamegraph much, because LZ4 compression is very fast and doesn’t need as much CPU time as the random number generation we already know about, but if it were the other way around the JFR flamegraph would be very misleading.

Even though the flamegraph now shows a complete picture of CPU time, it still points towards optimising random number generation, which we can’t do. The problem is now that CPU time isn’t always enough to understand latency.

Wallclock profiling

As used in Datadog’s profiler, async-profiler’s CPU profiler uses CPU time to schedule sampling, which means time spent off-CPU will not be sampled.

In Java Thread terms, a CPU profiler can only sample threads in the RUNNABLE state, and ignores threads in the BLOCKED, TIMED_WAITING, and WAITING states, but a wallclock profiler can sample threads in any state.

async-profiler also has a wallclock profiler, but we found we needed to tailor it to our requirements.

Sampling strategy

The first issue we encountered was with overhead (for our own particular requirements, don’t be discouraged from using async-profiler’s wallclock profiler in a different context). CPU profiling is always very lightweight because the overhead is proportional to the number of cores, whereas for wallclock profiling, overhead scales with the number of threads. async-profiler’s wallclock profiler samples sets of up to 8 threads round-robin, and to keep the sampling interval consistent as the number of threads changes, will adjust the sampling interval to as low 100 microseconds. Unless the user provides a thread filter expression to control how many threads to sample, the overhead of this approach can be quite high. Using a predefined thread filter assumes the user knows where the problems are ahead of time, and they might do when doing offline/non-continuous profiling. It can also produce quite large recordings: in 60s we might record as many as 4.8 million samples, which, at about 64 bytes per JFR event, corresponds to about 250MiB.

We wanted smaller recordings and needed to be very conservative about overhead, so we changed the way threads are sampled. We implemented reservoir sampling of threads so we could take a uniform sample of a fixed number of threads at a constant sampling interval. This gives a much more manageable upper bound on overhead and recording size: in 60s we can sample 16 threads at 100Hz and record at most 96,000 samples, which is just under 6MiB of JFR events. This approach reintroduces the problem async-profiler solves with its interval adjustment when the number of threads changes over time because this changes the probability of sampling a thread (the reservoir is fixed size), but this can be solved by recording the number of live threads each sample interval and upscaling later.

Tracer managed thread filter

High thread counts also can also reduce sample relevance, without a thread filter. For latency analysis it would be ideal to bias towards threads on the critical path. There are two kinds of noncritical threads for typical applications:

- idle threads in over-provisioned thread pools, each waiting for items to appear in a queue.

- background threads such as metrics reporters.

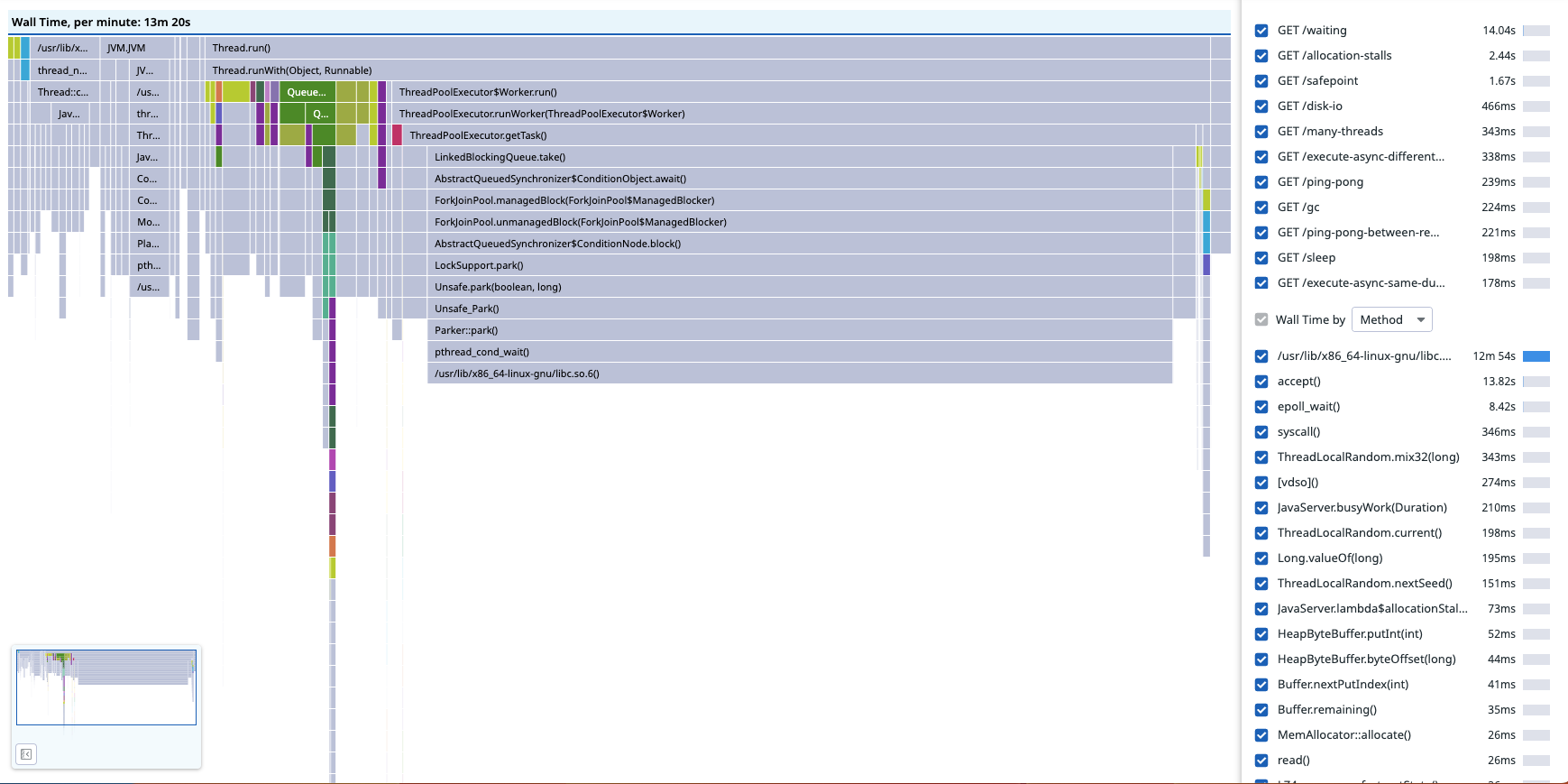

In the screenshot below, at least half of the samples are of the 200 workers (which is too many for this application) waiting for work to arrive on a LinkedBlockingQueue.

This isn’t very useful information: while fine-tuning the size of this thread pool would be generally beneficial, the threads aren’t blocking the threads processing requests.

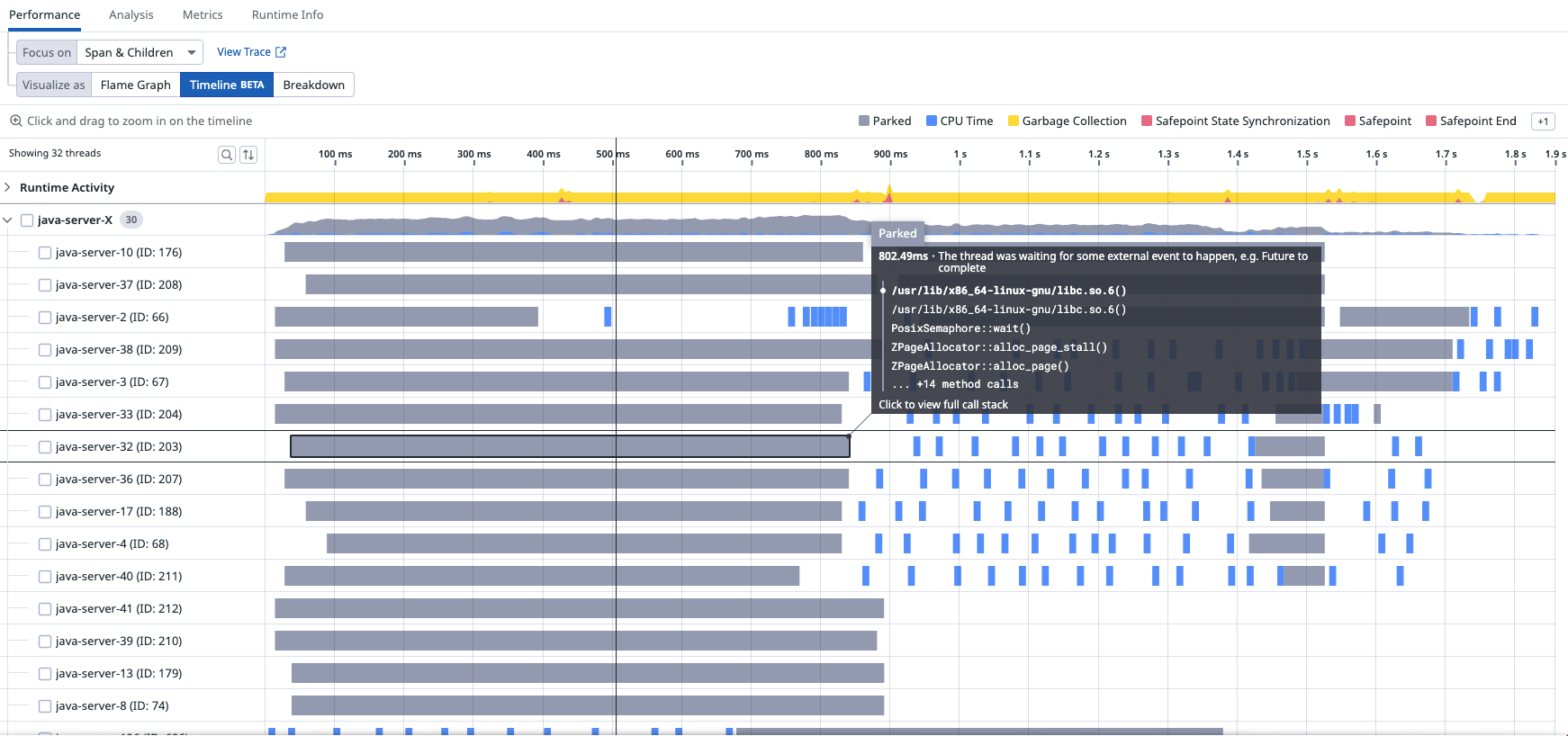

What’s worse is when the samples are rendered as a timeline of a particular trace, the coverage is quite sparse (the grey bars are PARKED walltime samples, the blue bars are CPU samples).

Sampling idle or background activity reduces the coverage of traces.

Both of these problems can be solved by only sampling threads which have an active trace context set up by the tracer. Firstly, tracing is designed to record request latency, so if there is a trace context associated with a thread for a time period, there is a good chance the work is being done to complete a request. Thanks to context propagation, which propagates trace context into thread pools, any thread which ends up working to complete the request can be sampled. Secondly, biasing sampling towards traced activity helps focus the profiler on explaining trace latency, so we have the situation where the tracer can tell you how long a request took, and there’s a good chance that there will be wallclock samples to explain why it took so long. Whenever we have too much work to do, we can do a better job by prioritising some tasks over others, and it’s the same for sampling threads.

This results in a flamegraph focused on latency-critical work:

and when we look at the timeline of a particular trace, we have much better coverage (i.e. more grey bars for more threads)

This is implemented by repurposing async-profiler’s thread filter, so that it is only applied to the wallclock profiler, and is controlled by the tracer. The current thread is added to a bitset of thread ids whenever the current thread has a trace associated with it, and removed from the bitset whenever the thread no longer has a trace associated with it. If you have used a tracing API, you will be familiar with spans (logical operations within traces) and scopes (activations of spans on a thread). The tracer pushes a scope to a stack whenever a span is activated on a thread, so that any subsequent spans can refer to the activated span as a parent. Modifying the bitset each time a scope is pushed or popped from the scope stack is the most obvious implementation, but would lead to very high overhead for certain async workloads. Instead, the bitset is updated only when the scope stack becomes empty or non-empty, which corresponds to whether there is some trace associated with the thread or not, which almost always reduces the number of bitset updates and never increases it. Finally, the sampler thread implements reservoir sampling over the bitset of traced threads, rather than over all threads.

Latency investigation

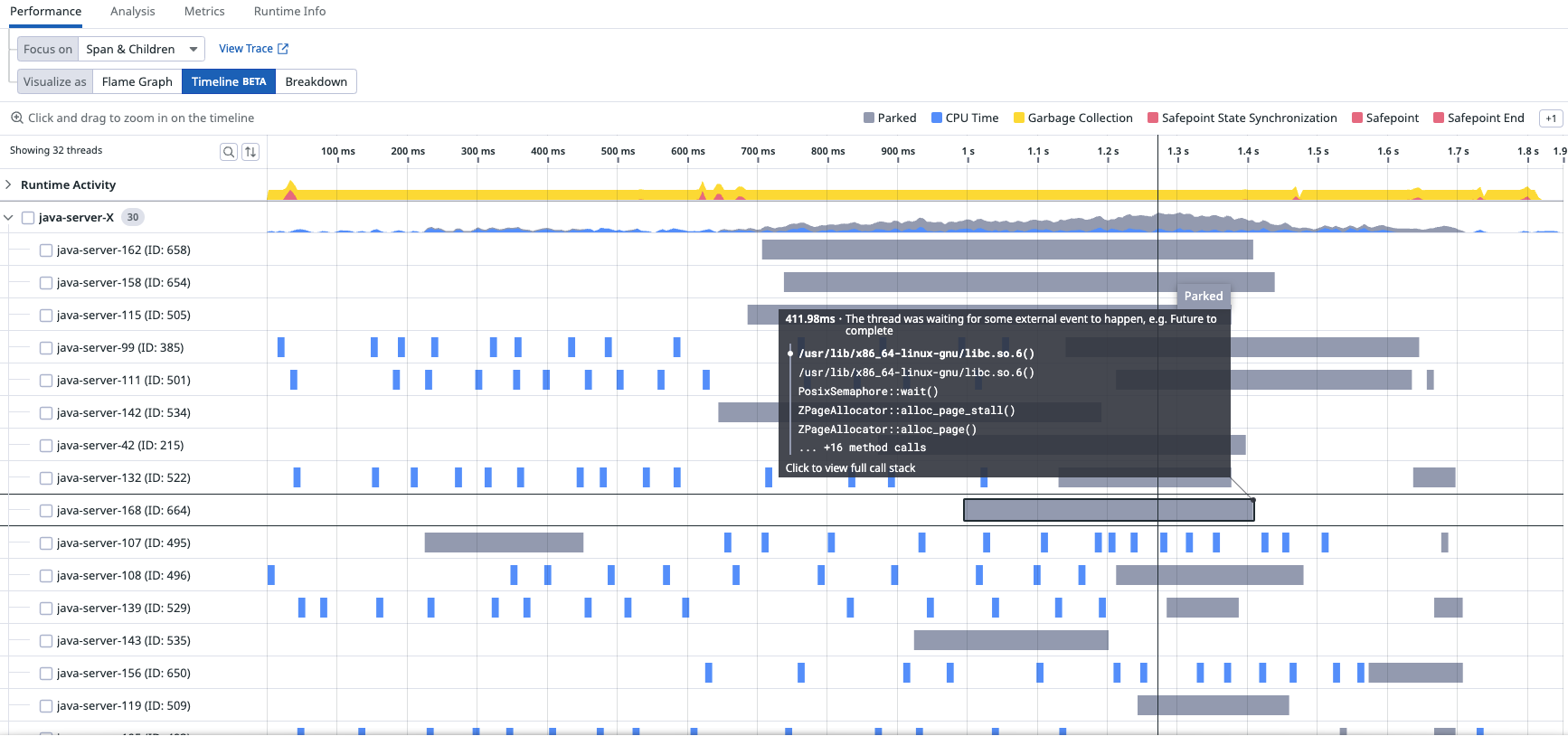

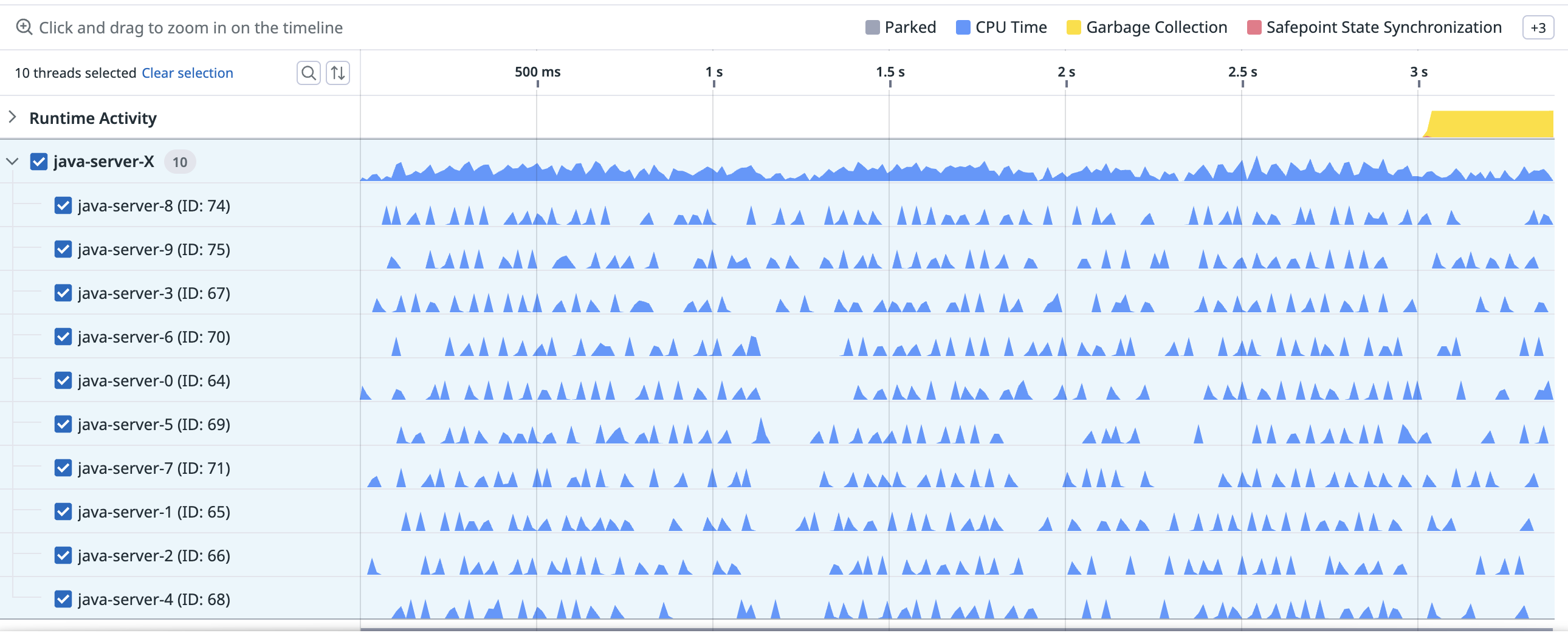

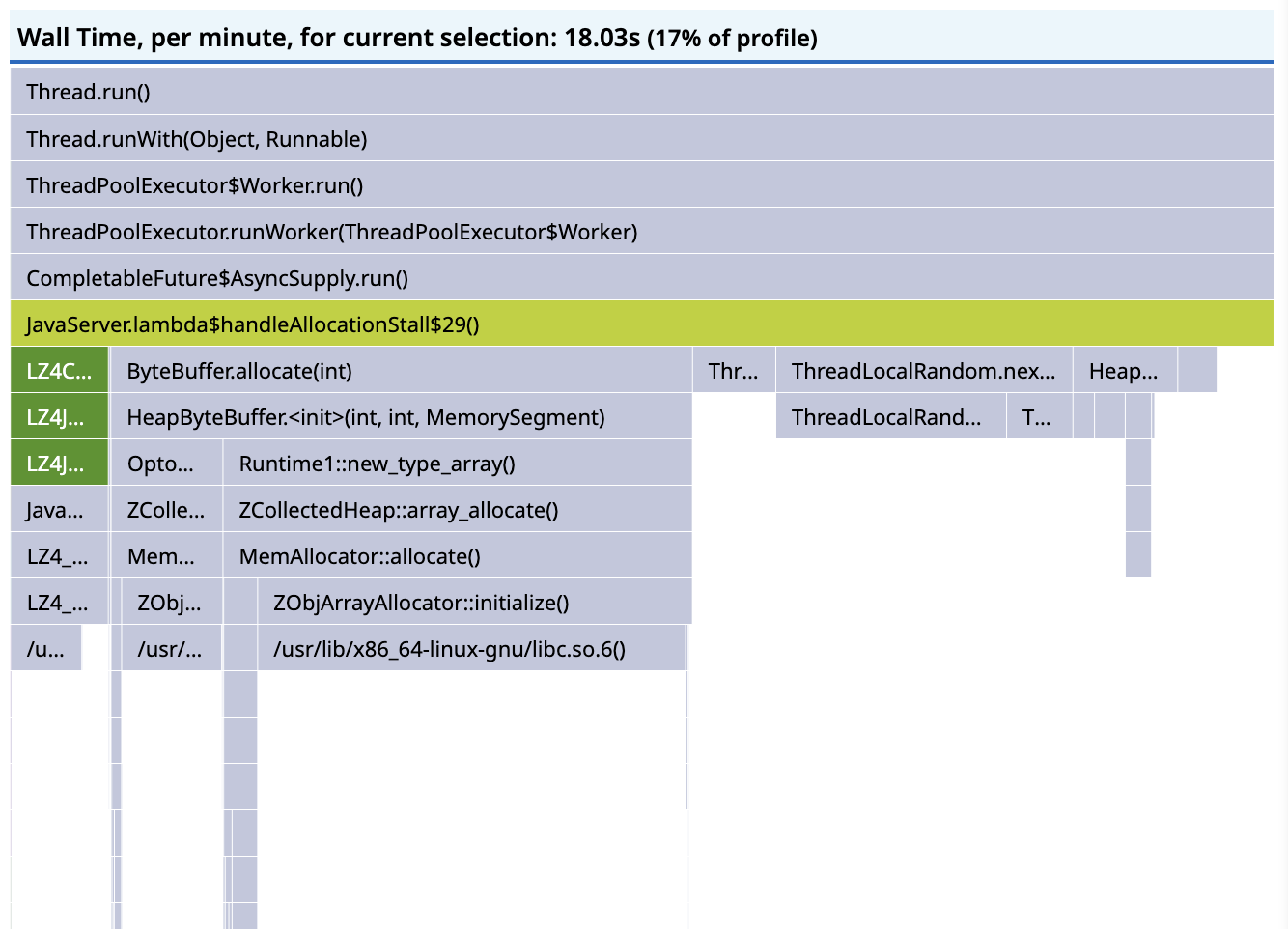

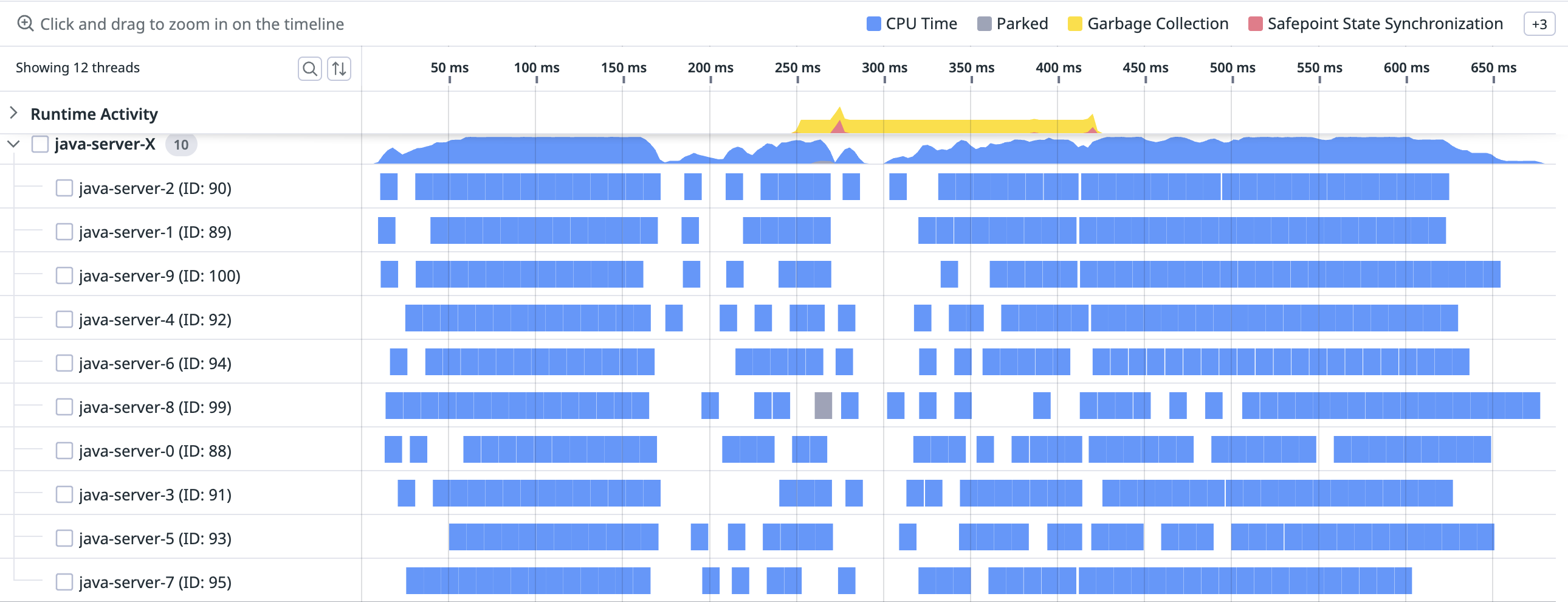

The wallclock profiler reports stack traces for any blocking off-CPU activity, which should tell you where the blocking operation happened, and why the blocking operation occurred by looking at the ancestor frames. It should have been possible to figure out why the request latency is so high from the screenshots so far, but here’s the timeline for a particular request trace again:

The long grey bars, with durations of about a second, all contain the frame ZPageAllocator::alloc_page_stall(), which blocks on PosixSemaphore::wait(), with causal ancestor frame ByteBuffer.allocate(int).

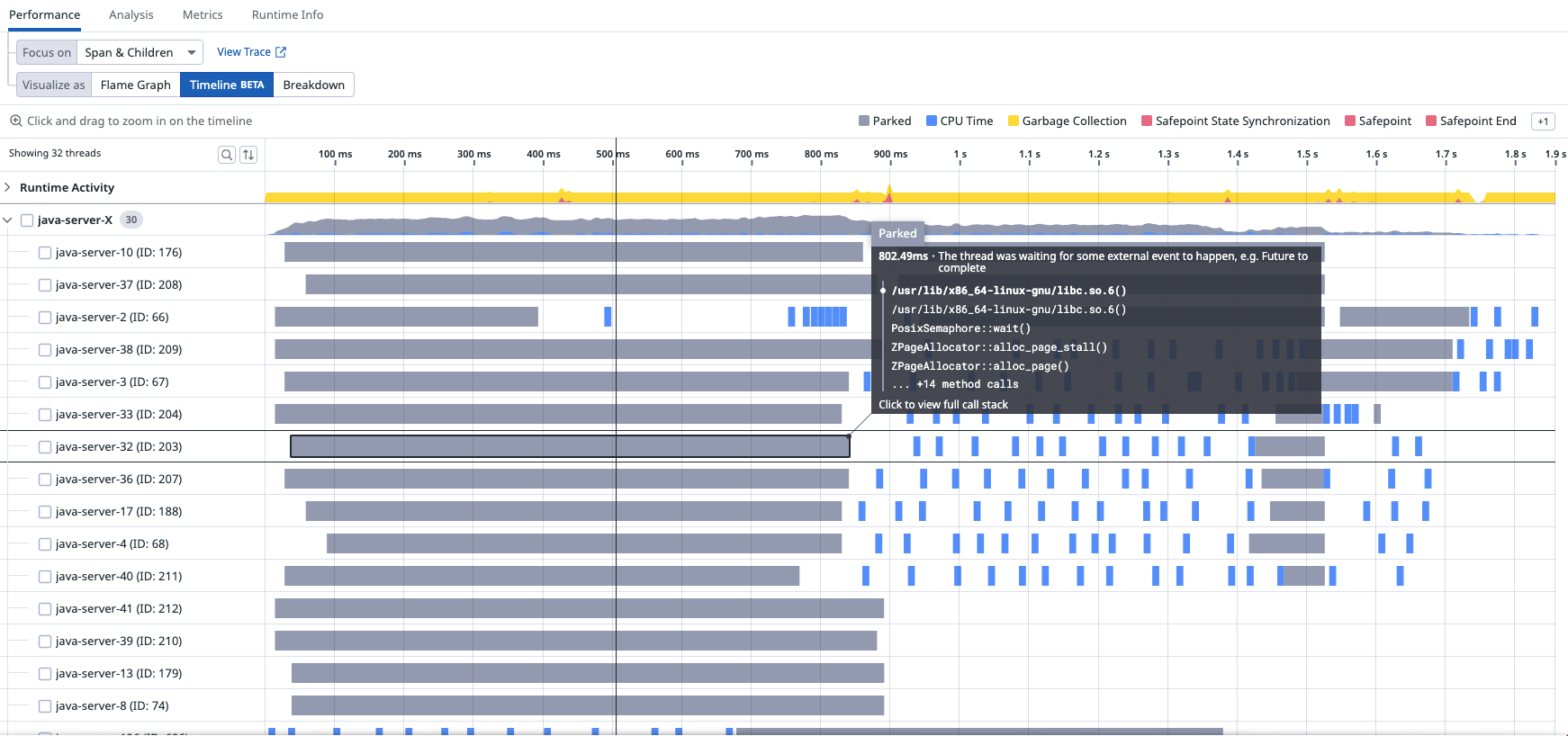

In the flamegraph scoped to the endpoint, we can see that about 50% of the samples under JavaServer.lambda$allocationStall$29() are allocation stalls, so the CPU profile missed roughly half the activity:

Allocation stalls happen with ZGC, when the application threads try to allocate more memory than is currently available. The application thread blocks until the requested allocation can be performed, which incurs latency. ZGC is effectively applying backpressure on the application threads, throttling concurrent access to memory as if it were a bounded queue, and it does this rather than OOM which is the only alternative. Allocation stalls are a symptom of an undersized heap, and there are two choices for mitigation: allocate a larger heap, or make the application allocate less.

In this contrived case, there are 30 tasks allocating a pair of 50 MiB ByteBuffers in a threadpool of 10 threads, which translates to 3GiB per request and 1000MiB allocated at any time during the request, with only 1GiB allocated to the heap.

Having identified and understood allocation stalls, we can see the heap is too small for the workload.

We can’t reduce allocation pressure by reducing the size of the buffers without renegotiating requirements, and we can’t reduce it by object pooling without blocking on the pool (we have less memory than we need) and our buffer pool might be less efficient than ZGC.

There is also a JFR event

jdk.ZAllocationStallwhich could be used instead of a wallclock profiler to determine that the heap is too small, but it does not collect stacktraces.

Increasing the heap size

Solving this problem should be a simple case of increasing the heap size so more memory can be allocated without stalling. The service should then become CPU bound, and it was already established that random number generation can’t be accelerated, so we wouldn’t be able to remove this bottleneck without redefining the workload.

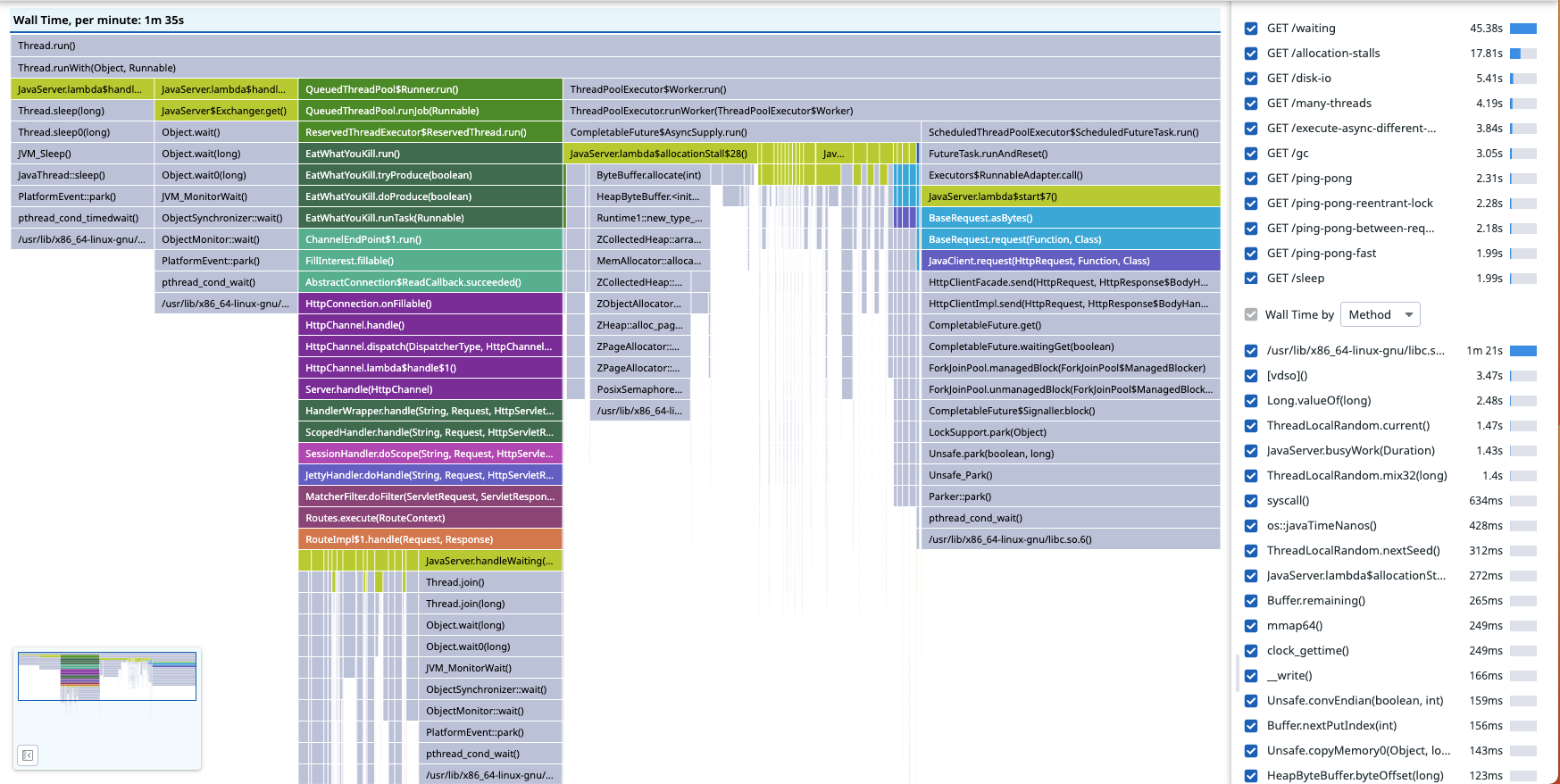

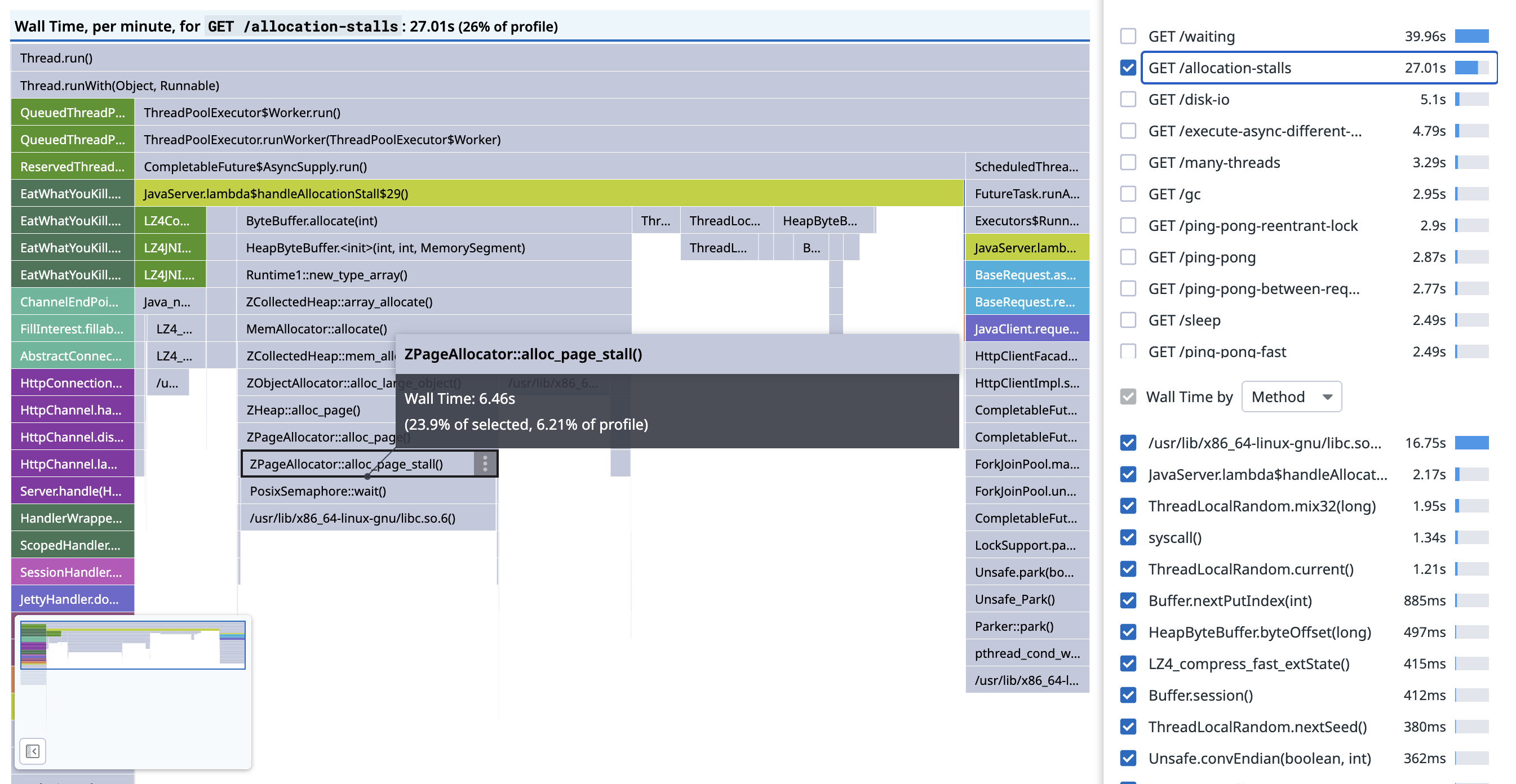

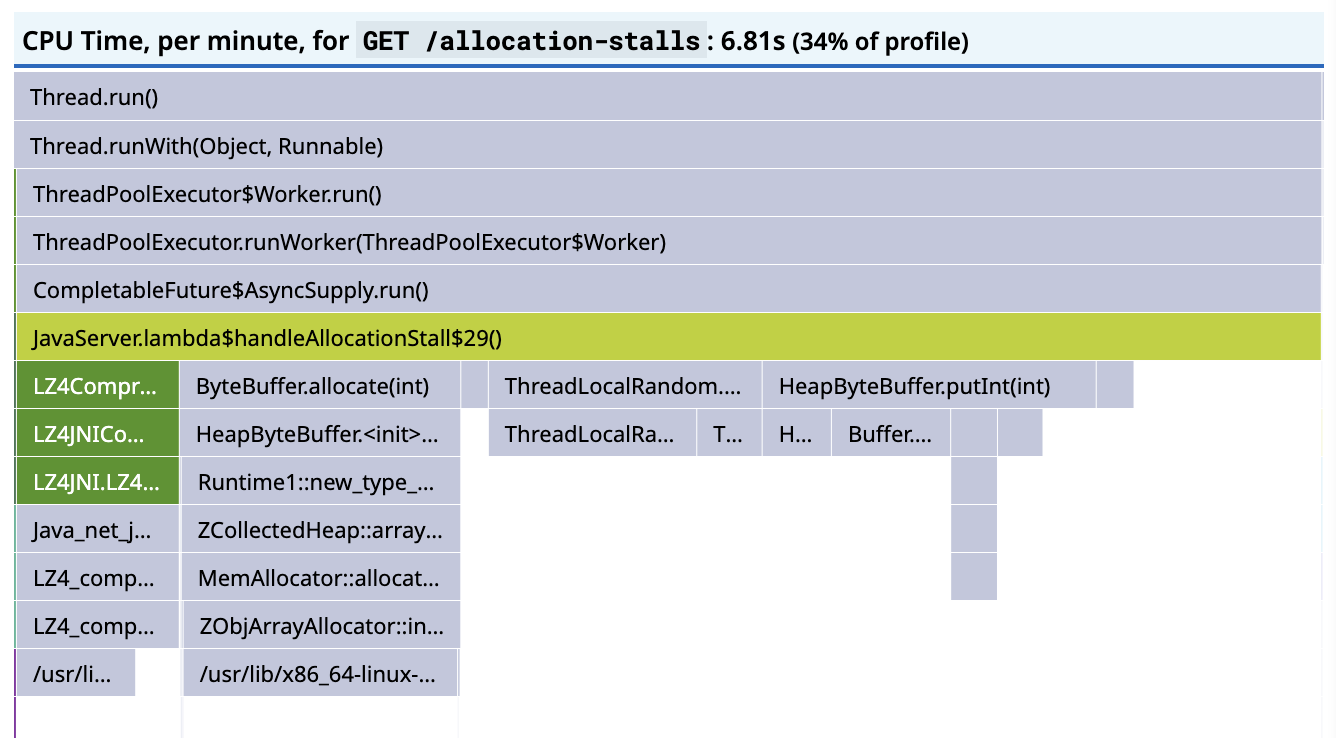

The heap size was increased to 6GiB. Looking at the wallclock profile, we can see a change in thread state:

Before, in the top image, about half the time was in the RUNNABLE state and half in the PARKED state, afterwards the split is 3:1.

The allocation stalls have gone, and none of the PARKED time is under the JavaServer.lambda$allocationStall$29() frame: the allocation stalls have disappeared.

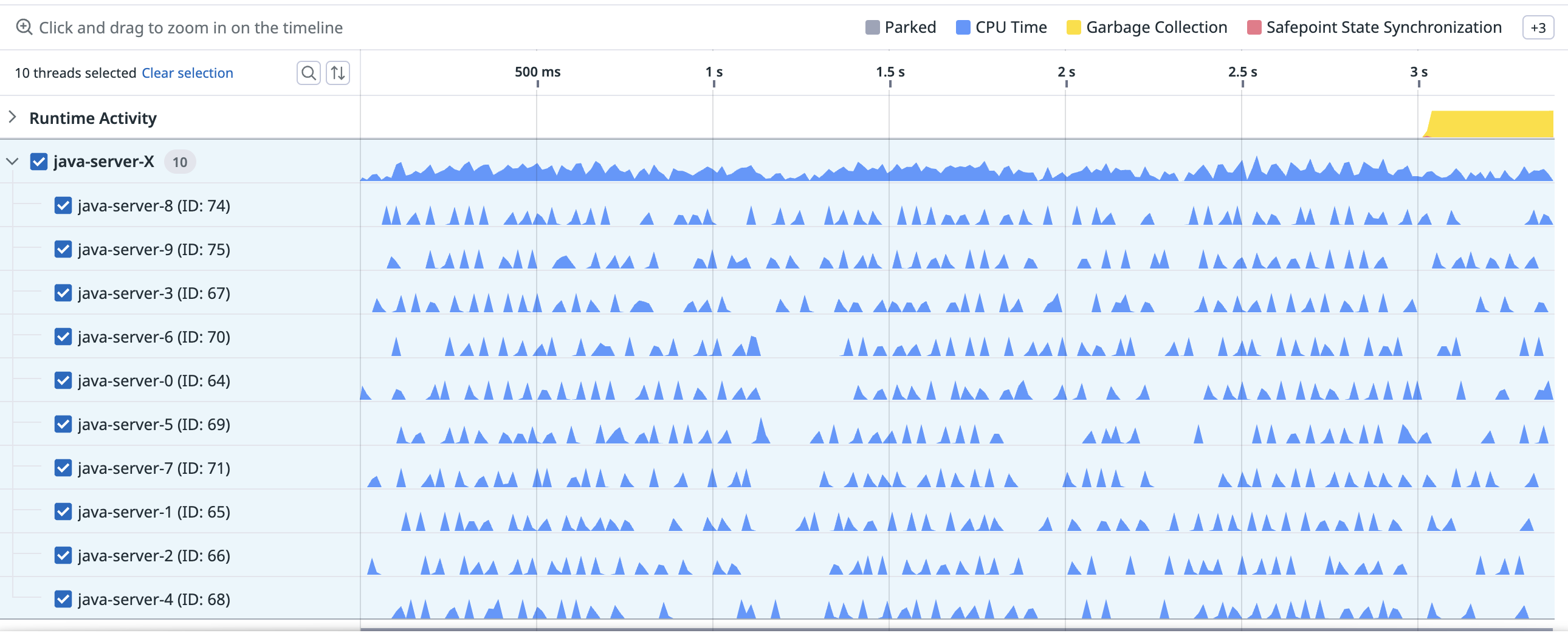

Looking at a trace of a particular request, the grey bars which represented parking have gone, and we only see the blue CPU samples:

It’s clear the way the JVM executes the code has changed as a result of being given more resources, but it hasn’t actually reduced latency.

Increasing the number of vCPUs

The clue about what to fix next is in the timeline for the request: the CPU samples are very sparse in time and across the threads.

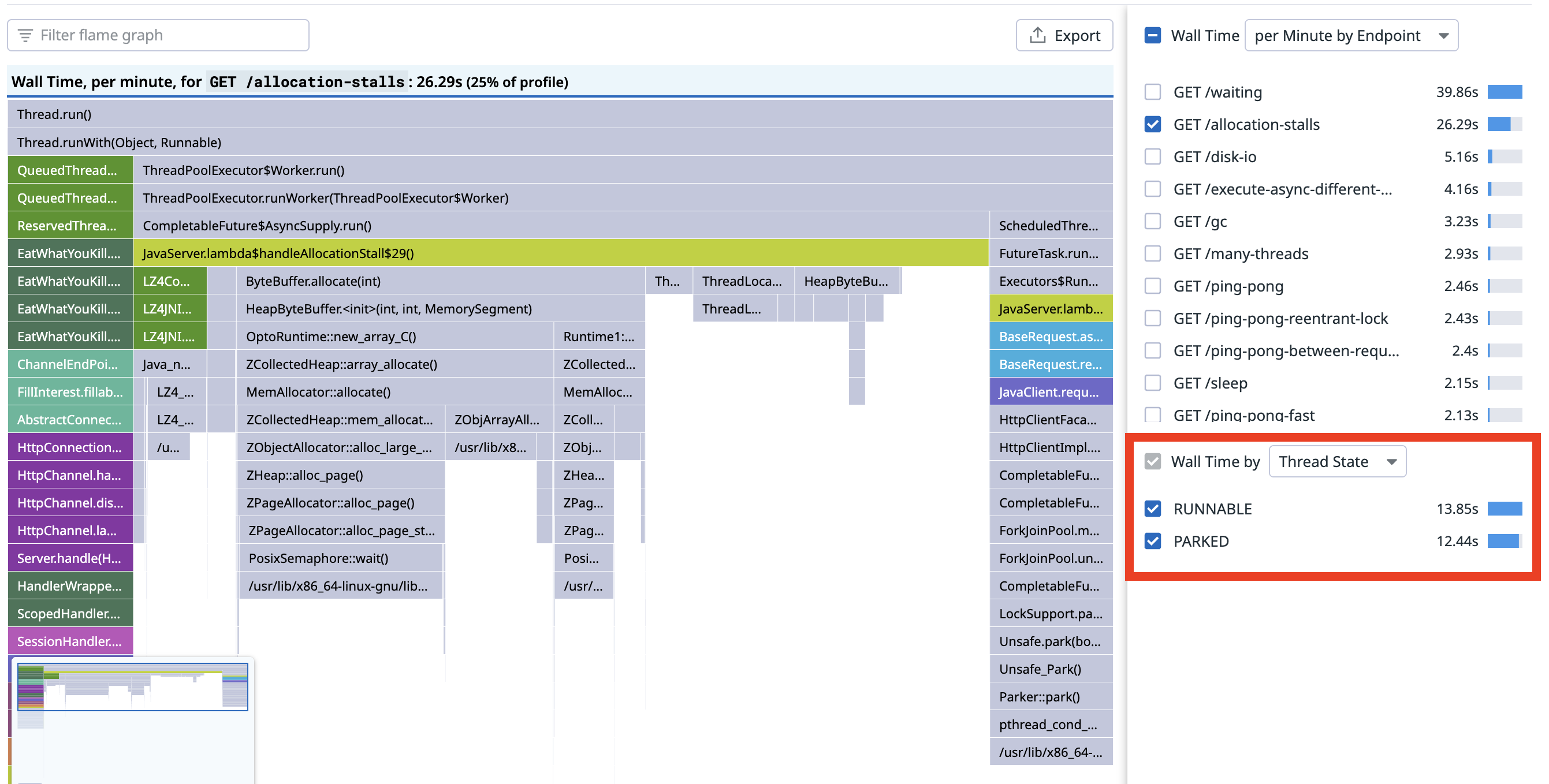

We can also see a strange discrepancy between the amount of wall time sampled in the RUNNABLE state and the amount of sampled CPU time:

If the workload is now CPU bound, as we expect it to be, and it’s actually executing, then the CPU time and the wall time should be the same, but there’s 18 seconds of RUNNABLE wall time and less than 5s of CPU time.

Though we don’t have a direct way to show it, this indicates that the threads are competing to get scheduled on too few vCPUs, and if we could allocate more CPU to the container, the responses should become CPU bound.

As can be seen in the timeline, the workload is parallelised over 10 threads, but only 2 vCPUs were allocated.

Increasing the number of vCPUs to 10, finally, reduces latency dramatically:

Though they will never correspond exactly, the sampled RUNNABLE wall time and CPU times have converged:

and the timeline for a particular trace shows 10 threads with denser blue CPU samples:

What about cost?

This probably isn’t very satisfying: the cost of the running service has been increased dramatically. However, the aim was to reduce request latency for a contrived workload that isn’t amenable to optimisations. When code is at its efficient frontier (or effectively at its efficient frontier without, say, incurring huge engineering costs), there is a tradeoff between latency and cost. If you don’t have an SLA, you can just run this workload on 2vCPUs and a 1GiB heap for very little cost, and though ZGC will throttle allocations and it will be slow, things will basically work. If you do have an SLA, and optimisation is impractical or impossible, and you can’t negotiate requirements, you’ll need to incur costs and allocate more compute resources. It’s quite rare for a Java service to be at its efficient frontier, and there’s usually low hanging fruit surfaced by continuous profiling which can sometimes reduce latency and cost simultaneously.