Limiting Factors in a Dot Product Calculation

The dot product is a simple calculation which reduces two vectors to the sum of their element-wise products. The calculation has a variety of applications and is used heavily in neural networks, linear regression and in search. What are the constraints on its computational performance? The combination of the computational simplicity and its streaming nature means the limiting factor in efficient code should be memory bandwidth. This is a good opportunity to look at the raw performance that will be made available with the vector API when it’s released.

Since Java 9, a dot product calculation can use the Math.fma intrinsic.

public float vanilla() {

float sum = 0f;

for (int i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

sum = Math.fma(left[i], right[i], sum);

}

return sum;

}

Despite its simplicity, this code is incredibly inefficient precisely because it’s written in Java. Java is a language which prizes portability, sometimes at the cost of performance. The only way to make this routine produce the same number given the same input, no matter what operating system or instruction sets are available, is to do the operations in the same order, which means no unrolling or vectorisation. For a web application, this a good trade off, but for data analytics it is not.

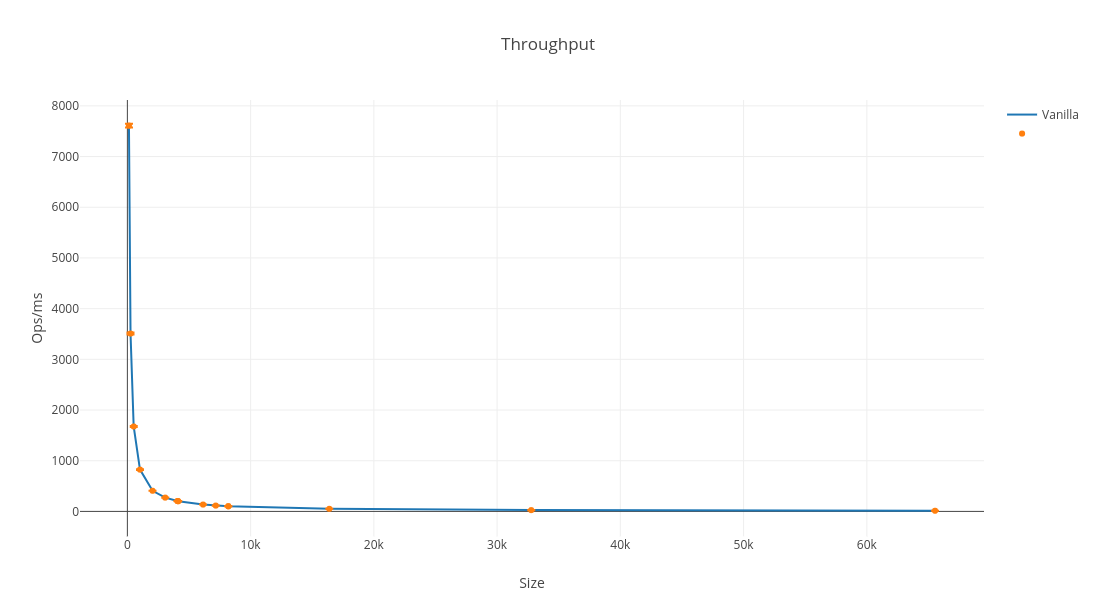

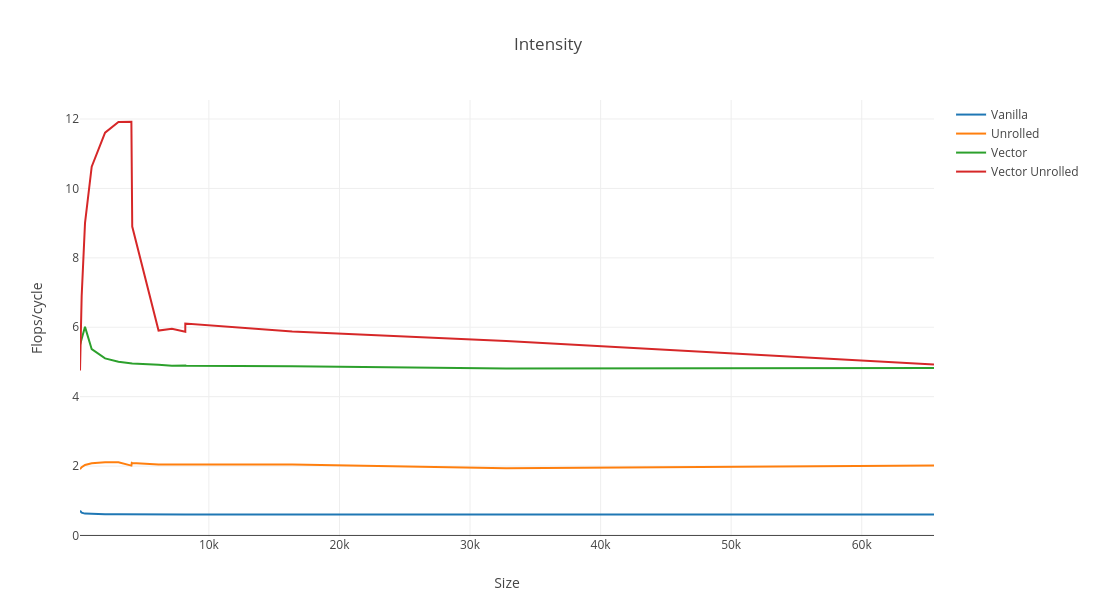

An estimate of intensity, assuming a constant processor frequency, and two floating point operations (flops) per FMA, shows that the intensity is constant but very low at 0.67 flops/cycle. There being constant intensity as a function of array size is interesting because it indicates that the performance is insensitive to cache hierarchy, that the the limit is the CPU. Daniel Lemire made this observation with a benchmark written in C, disabling fastmath compiler optimisations, recently.

The JLS’s view on floating point arithmetic is the true limiting factor here. Assuming you really care about dot product performance, the best you can do to opt out is to unroll the loop and get slightly higher throughput.

public float unrolled() {

float s0 = 0f;

float s1 = 0f;

float s2 = 0f;

float s3 = 0f;

float s4 = 0f;

float s5 = 0f;

float s6 = 0f;

float s7 = 0f;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i += 8) {

s0 = Math.fma(left[i + 0], right[i + 0], s0);

s1 = Math.fma(left[i + 1], right[i + 1], s1);

s2 = Math.fma(left[i + 2], right[i + 2], s2);

s3 = Math.fma(left[i + 3], right[i + 3], s3);

s4 = Math.fma(left[i + 4], right[i + 4], s4);

s5 = Math.fma(left[i + 5], right[i + 5], s5);

s6 = Math.fma(left[i + 6], right[i + 6], s6);

s7 = Math.fma(left[i + 7], right[i + 7], s7);

}

return s0 + s1 + s2 + s3 + s4 + s5 + s6 + s7;

}

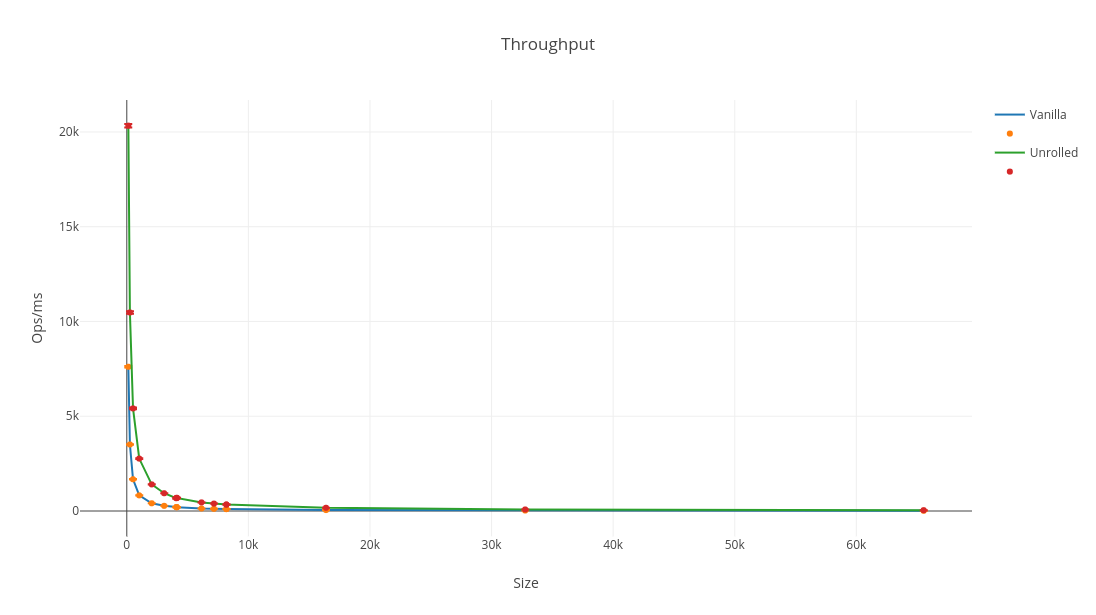

The intensity is about 4x better, but still constant. My Intel Skylake processor is capable of 32 flops/cycle, so this code is clearly still not very efficient, but it’s actually the best you can do with any released version of OpenJDK at the time of writing.

The Vector API

I have been keeping an eye on the Vector API incubating in Project Panama for some time, and have only recently got round to kicking the tires. I wrote some benchmarks earlier in the year but ran into, as one should expect of a project in active development, bugs in FMA and vector box elimination. This limited the value I would get from writing about the benchmarks. These bugs have been fixed for a long time now, and you can start to see the how good this API is going to be.

Here’s a simple implementation which wouldn’t be legal for C2 (or Graal for that matter) to generate from the dot product loop. It relies on an accumulator vector, into which a vector dot product of the next eight elements is FMA’d for each step of the loop.

public float vector() {

var sum = YMM_FLOAT.zero();

for (int i = 0; i < size; i += YMM_FLOAT.length()) {

var l = YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(left, i);

var r = YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(right, i);

sum = l.fma(r, sum);

}

return sum.addAll();

}

This loop can be unrolled, but it seems that this must be done manually for the sake of stability. The unroll below uses four accumulators and results in a huge boost in throughput.

private float vectorUnrolled() {

var sum1 = YMM_FLOAT.zero();

var sum2 = YMM_FLOAT.zero();

var sum3 = YMM_FLOAT.zero();

var sum4 = YMM_FLOAT.zero();

int width = YMM_FLOAT.length();

for (int i = 0; i < size; i += width * 4) {

sum1 = YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(left, i).fma(YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(right, i), sum1);

sum2 = YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(left, i + width).fma(YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(right, i + width), sum2);

sum3 = YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(left, i + width * 2).fma(YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(right, i + width * 2), sum3);

sum4 = YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(left, i + width * 3).fma(YMM_FLOAT.fromArray(right, i + width * 3), sum4);

}

return sum1.addAll() + sum2.addAll() + sum3.addAll() + sum4.addAll();

}

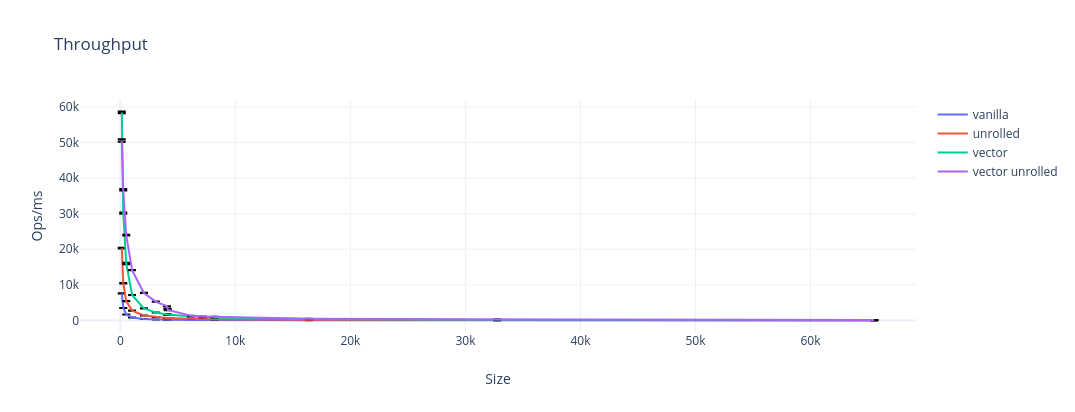

This plot doesn’t quite do justice to how large the difference is. In fact, presenting the data like this is a great way to mislead people! It looks better on a log scale.

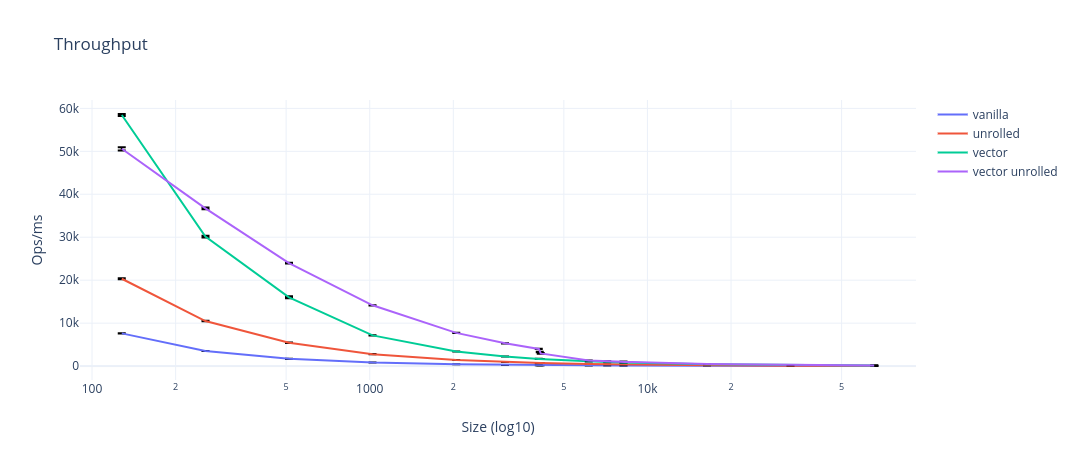

Whilst the absolute difference narrows, the relative performance is more or less constant. Looking at intensity gives a much better picture and is size invariant (until memory bandwidth is saturated).

The first thing to notice is that the intensity gets nowhere near 32 flops/cycle, and that’s because my chip can’t load data fast enough to keep the two FMA ports busy. Skylake chips can do two loads per cycle, which is enough for one FMA between two vectors and the accumulator. Since the arrays are effectively streamed, there is no chance to reuse any loads, so the absolute maximum intensity is 50% capacity, or just 16 flops/cycle.

In the unrolled vector code, the intensity hits 12 flops/cycle just before 4096 elements. 4096 is a special number because 2 * 4096 * 4 = 32kB is the capacity of L1 cache. This peak and rapid decrease suggests that the code is fast enough to be hitting memory bandwidth: if L1 were larger or L2 were faster, the intensity could be sustained. This is great, and the performance counters available with -prof perfnorm corroborate.

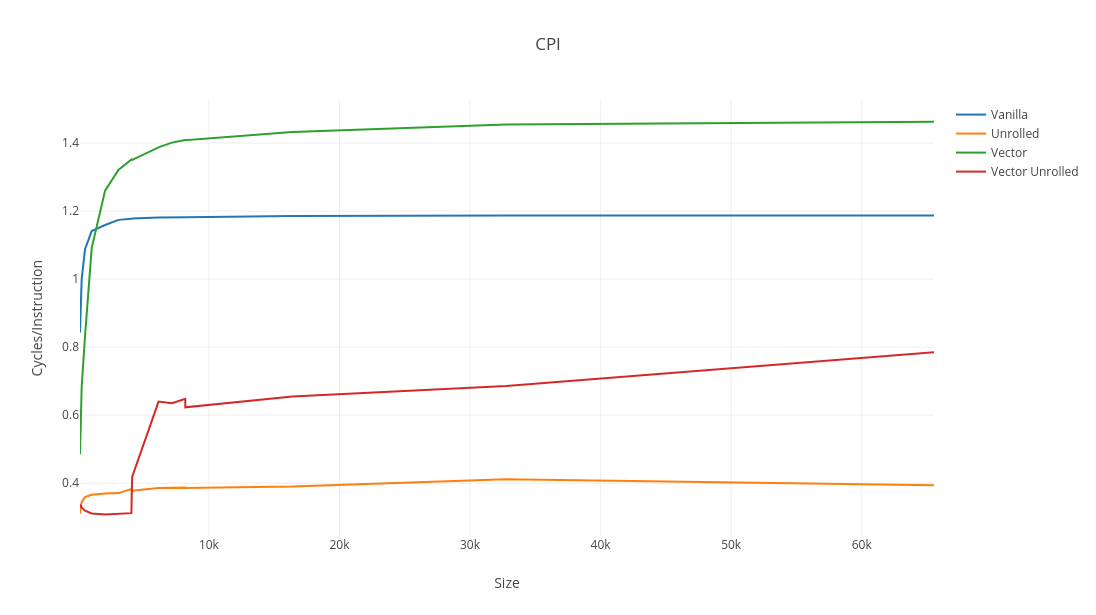

In the vanilla loop and unrolled loop, the cycles per instruction (CPI) reaches a maximum long before the arrays breach L1 cache. The latency of an instruction depends on where its operands come from, increasing the further away from L1 cache the data comes from. If CPI for arrays either side of the magical 4096 element threshold is the same, then memory cannot be the limiting factor. The unrolled vector loop show a very sharp increase, suggesting a strong dependency on load speed. Similarly, L1-dcache-load-misses can be seen to increase sharply once the arrays are no longer L1 resident (predictably) correlated with a drop in intensity only in the vector unrolled implementation. It’s short lived, but the unrolled vector code, albeit with bounds checks disabled, is efficient enough for the CPU not to be the bottleneck.

See the benchmarks and raw data. The JDK used was built from the vectorIntrinsics branch of the Project Panama OpenJDK fork, run with JMH 1.20 on Ubuntu 16.04 LTS, on a 4 core i7-6700HQ processor.