Tuning Spark Back Pressure by Simulation

Spark back pressure, which can be enabled by setting spark.streaming.backpressure.enabled=true, will dynamically resize batches so as to avoid queue build up. It is implemented using a Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) algorithm. This algorithm has some interesting properties, including the lack of guarantee of a stable fixed point. This can manifest itself not just in transient overshoot, but in a batch size oscillating around a (potentially optimal) constant throughput. The overshoot incurs latency; the undershoot costs throughput. Catastrophic overshoot leading to OOM is possible in degenerate circumstances (you need to choose the parameters quite deviously to cause this to happen). Having witnessed undershoot and slow recovery in production streaming jobs, I decided to investigate further by testing the algorithm with a simulator. This is very simple to do with JUnit by creating an instance of a PIDRateEstimator and calling its methods within a simulation loop.

PID Controllers

The PID controller is a closed feedback loop on a single process variable, which it aims to stabilise (but may not be able to) by minimising three error metrics - present error (w.r.t. the last measurement), accumulated or integral error, and the rate at which the error is changing, or derivative error. The total signal is a weighted sum of these factors.

\[u(t) = K_{p}e(t) + K_{i}\int_{0}^{t} e(\tau) d\tau + K_{d}\frac{d}{dt}e(t)\]The $K_{p}$ term aims to react to any immediate error, the $K_{i}$ term dampens change in the process variable, and the $K_{d}$ amplifies any trend to react to underlying changes quickly. Spark allows these parameters to be tuned by setting the following environment variables

- $K_{p}$

spark.streaming.backpressure.pid.proportional(defaults to 1, non-negative) - weight for the contribution of the difference between the current rate with the rate of the last batch to the overall control signal. - $K_{i}$

spark.streaming.backpressure.pid.integral(defaults to 0.2, non-negative) - weight for the contribution of the accumulation of the proportional error to the overall control signal. - $K_{d}$

spark.streaming.backpressure.pid.derived(defaults to zero, non-negative) - weight for the contribution of the change of the proportional error to the overall control signal.

The default values are typically quite good. You can set an additional parameter not present in classical PID controllers: spark.streaming.backpressure.pid.minRate - the default value is 100 (must be positive). This is definitely a variable to watch out for if you are using back-pressure and have up front knowledge that you are expected to process messages at a rate much higher than 100; you can improve stability by minimising undershoot.

Constant Throughput Simulator

Consider the case where all else is held equal and a job will execute at a constant rate, with batches scheduled at a constant frequency. The size of the batch is allowed to vary according to back pressure, but the rate is constant. These assumptions negate the proportional amortization of fixed overhead in larger batches (economy of scale), and any extrinsic fluctuation in rate. The goal of the algorithm is to find, in a reasonable number of iterations, a stable fixed point for the batch size, close to the constant rate implied by the frequency. Depending on your batch interval, this may be a long time in real terms. The test is useful in two ways

- Evaluating the entire parameter space of the algorithm: finding toxic combinations of parameters and initial throughputs which lead to divergence, oscillation or sluggish convergence.

- Optimising parameters for a use case: for a given expected throughput rate, rapidly simulate the job under backpressure to optimise the choice of parameters.

Running a simulator is faster than running Spark jobs with production data repeatedly so can be useful for tuning the parameters. The suggested settings need to be validated afterwards by testing on an actual cluster.

- Fix a batch interval and a target throughput.

- Choose a range possible values for $K_{p}$, $K_{i}$, $K_{d}$ between zero and two.

- Choose a range of initial batch sizes (as in

spark.streaming.receiver.maxRate), above and below the size implied by the target throughput and frequency. - Choose some minimum batch sizes to investigate the effect on damping.

- Run a simulation for each element of the cartesian product of these parameters.

- Verify the simulation by running a Spark streaming job using the recommended parameters.

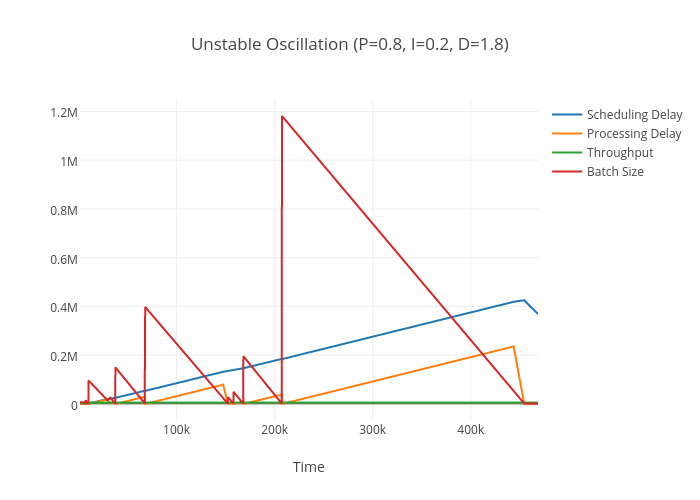

From 4000 test cases, I found over 500 conditions where the algorithm oscillated violently out of control, despite maintaining constant throughput, typically when the integral and derivative components are large.

In a real Spark Streaming job this would result in an OOM. When I get time I will try to find a mathematical justification for this to verify this isn’t a bug in the simulator.

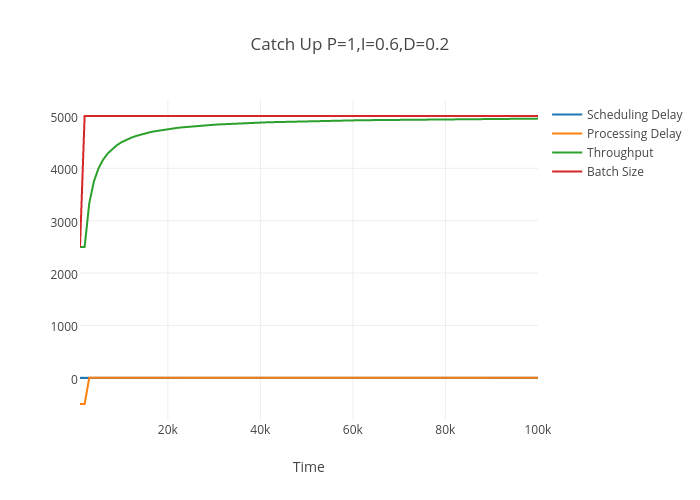

There are also interesting cases where the algorithm is stable and convergent. The first is catching up from a conservative estimate of throughput - which seems across a range of parameters not to overshoot.

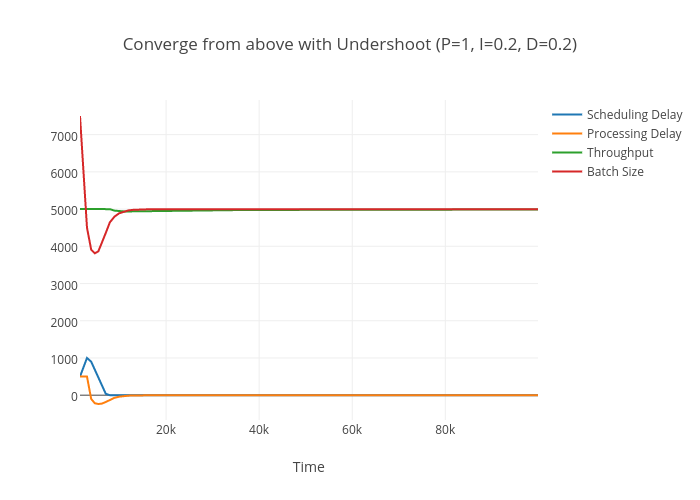

When the algorithm needs to slow down it will always undershoot before converging. This cost will be amortized as will the latency incurred. However, if throughput is preferred it is better to overestimate the initial batch; if latency is preferred it is better to underestimate.

Simulator Code

@RunWith(Parameterized.class)

public class TestPIDController {

@Parameterized.Parameters(name = "Aim for {5}/s starting from initial batch={6} with interval {0}s, p={1}, i={2}, d={3}")

public static Object[][] generatedParams() {

double requiredThroughput = 5000;

long maxlatency = 1L;

double[] proportionals = new double[10];

double[] integrals = new double[10];

double[] derivatives = new double[10];

double v = 0.0;

for(int j = 0; j < proportionals.length; ++j) {

proportionals[j] = v;

integrals[j] = v;

derivatives[j] = v;

v += 2D/proportionals.length;

}

double[] initialBatchSizes = new double[] { 2500, 4500, 5500, 7500 };

double[] minBatchSizes = new double[] { 100, 500, 1000, 2500, 4500};

int numTestCases = proportionals.length * integrals.length * derivatives.length * initialBatchSizes.length;

Object[][] cases = new Object[numTestCases][];

for(int caseNum = 0; caseNum < numTestCases; ++caseNum) {

cases[caseNum] = new Object[7];

cases[caseNum][0] = maxlatency;

cases[caseNum][5] = requiredThroughput;

}

for(int caseNum = 0; caseNum < numTestCases; ++caseNum) {

cases[caseNum][1] = proportionals[caseNum % proportionals.length];

}

Arrays.sort(cases, (a, b) -> (int)(20 *(double)a[1] - 20 * (double)b[1]));

for(int caseNum = 0; caseNum < numTestCases; ++caseNum) {

cases[caseNum][2] = integrals[caseNum % integrals.length];

}

Arrays.sort(cases, (a, b) -> (int)(20 * (double)a[2] - 20 * (double)b[2]));

for(int caseNum = 0; caseNum < numTestCases; ++caseNum) {

cases[caseNum][3] = derivatives[caseNum % derivatives.length];

}

Arrays.sort(cases, (a, b) -> (int)(20 * (double)a[3] - 20 * (double)b[3]));

for(int caseNum = 0; caseNum < numTestCases; ++caseNum) {

cases[caseNum][4] = minBatchSizes[caseNum % minBatchSizes.length];

}

Arrays.sort(cases, (a, b) -> (int)((double)a[4] - (double)b[4]));

for(int caseNum = 0; caseNum < numTestCases; ++caseNum) {

cases[caseNum][6] = initialBatchSizes[caseNum % initialBatchSizes.length];

}

Arrays.sort(cases, (a, b) -> (int)((double)a[6] - (double)b[6]));

return cases;

}

public TestPIDController(long batchSizeSeconds,

double proportional,

double summation,

double derivative,

double minRate,

double constantProcessingRate,

double initialBatchSize) {

this.expectedBatchDurationSeconds = batchSizeSeconds;

this.proportional = proportional;

this.summation = summation;

this.derivative = derivative;

this.minRate = minRate;

this.constantProcessingRatePerSecond = constantProcessingRate;

this.initialBatchSize = initialBatchSize;

}

private final long expectedBatchDurationSeconds;

private final double proportional;

private final double summation;

private final double derivative;

private final double minRate;

private final double constantProcessingRatePerSecond;

private final double initialBatchSize;

@Test

public void ensureRapidConvergence() {

System.out.println("Time,Scheduling Delay,Processing Delay,Throughput,Batch Size");

long schedulingDelayMillis = 0;

double batchSize = initialBatchSize;

long expectedBatchDurationMillis = 1000 * expectedBatchDurationSeconds;

double batchTimeSeconds;

long batchTimeMillis;

long timeMillis = 0;

PIDRateEstimator estimator = new PIDRateEstimator(expectedBatchDurationMillis, proportional, summation, derivative, minRate);

Option<Object> newSize;

double numProcessed = 0;

double throughput = Double.NaN;

for(int i = 0; i < 100; ++i) { // sanity check

if(timeMillis > 200 * expectedBatchDurationMillis)

Assert.fail();

numProcessed += batchSize;

batchTimeSeconds = getTimeToCompleteSeconds(batchSize);

batchTimeMillis = (long)Math.ceil(batchTimeSeconds * 1000);

long pauseTimeMillis = schedulingDelayMillis == 0 && batchTimeSeconds <= expectedBatchDurationSeconds ? expectedBatchDurationMillis - batchTimeMillis : 0;

timeMillis += batchTimeMillis + pauseTimeMillis;

newSize = estimator.compute(timeMillis, (long)batchSize, batchTimeMillis, schedulingDelayMillis);

if(newSize.isDefined()) {

batchSize = (double)newSize.get();

}

long processingDelay = batchTimeMillis - expectedBatchDurationMillis;

schedulingDelayMillis += processingDelay;

if(schedulingDelayMillis < 0) schedulingDelayMillis = 0;

throughput = numProcessed/timeMillis*1000;

System.out.println(String.format("%d,%d,%d,%f,%d", timeMillis,schedulingDelayMillis, processingDelay, throughput,(long)batchSize));

}

double percentageError = 100 * Math.abs((constantProcessingRatePerSecond - throughput) /

constantProcessingRatePerSecond);

Assert.assertTrue(String.format("Effective rate %f more than %f away from target throughput %f",

throughput, percentageError, constantProcessingRatePerSecond), percentageError < 10);

}

private double getTimeToCompleteSeconds(double batchSize) {

return batchSize / (constantProcessingRatePerSecond);

}

}

Response to Instantaneous and Sustained Shocks

There is an important feature of a control algorithm I haven’t simulated yet - how does the algorithm respond to random extrinsic shocks, both instantaneous and sustained. An instantaneous shock should not move the process variable away from its fixed point for very long. Under a sustained shock, the algorithm should move the process variable to a new stable fixed point.