Loop Fission

Loop fission is a process normally applied by a compiler to loops to make them faster. The idea is to split larger loop bodies which perform several distinct tasks into separate loops, in the hope that the individual loops can be optimised more effectively in isolation. As far as I’m aware, C2, Hotspot’s JIT compiler, doesn’t do this so you have to do it yourself. I came across a couple of cases where this was profitable recently, and this post uses these as examples.

XOR

One of the operations which can be performed between two RoaringBitmap objects is an XOR or symmetric difference.

After applying a destructive (i.e. one of the bitmaps will be mutated) XOR between two bitmaps, the mutated bitmap will contain a bit wherever the bitmaps differed before the XOR.

One of the three container types in a RoaringBitmap is a BitmapContainer which contains a bitmap, a dense collection of bits.

When a destructive XOR is applied between two BitmapContainers, the mutated container must have its bits updated, but they also need to be counted.

This can be done in one loop or two separate loops, as in the representative benchmark below:

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

public class XorCount {

@Param({"256", "512", "1024", "2048", "4096"})

int size;

private long[] left;

private long[] right;

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void setup() {

left = new long[size];

right = new long[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

left[i] = ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextLong();

right[i] = ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextLong();

}

}

@Benchmark

public int fused() {

int count = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < left.length & i < right.length; i++) {

left[i] ^= right[i];

count += Long.bitCount(left[i]);

}

return count;

}

@Benchmark

public int fissured() {

for (int i = 0; i < left.length & i < right.length; i++) {

left[i] ^= right[i];

}

int count = 0;

for (long l : left) {

count += Long.bitCount(l);

}

return count;

}

}

It seems intuitive that fused would be faster; there is only one pass over the data, but this isn’t necessarily the case.

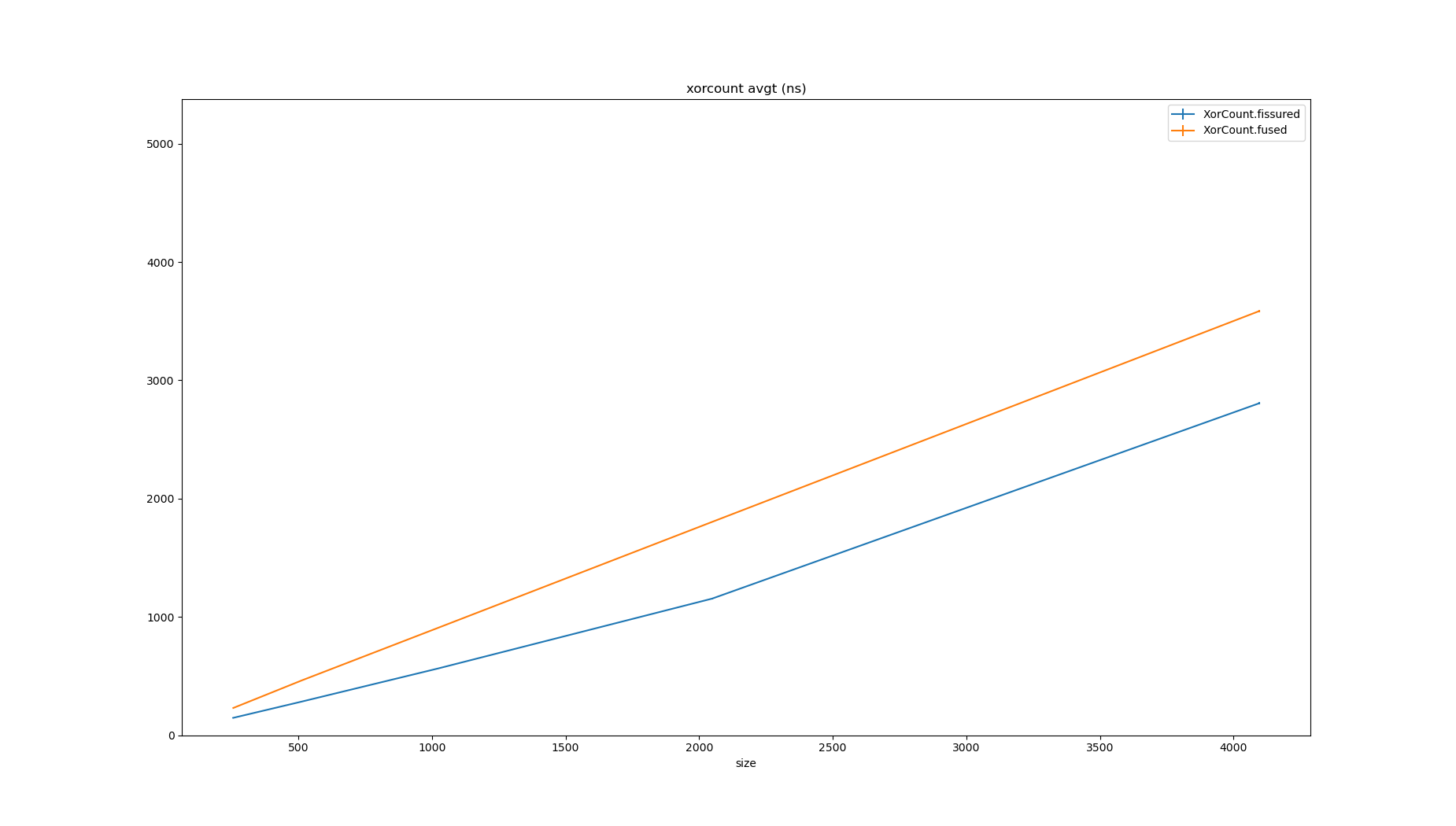

| Benchmark | Mode | Threads | Samples | Score | Score Error (99.9%) | Unit | Param: size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XorCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 146.324870 | 0.166643 | ns/op | 256 |

| XorCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 283.583423 | 0.156367 | ns/op | 512 |

| XorCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 564.507047 | 0.512299 | ns/op | 1024 |

| XorCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1154.083245 | 6.005591 | ns/op | 2048 |

| XorCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 2805.933619 | 10.880235 | ns/op | 4096 |

| XorCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 229.713707 | 0.138824 | ns/op | 256 |

| XorCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 462.435821 | 1.015399 | ns/op | 512 |

| XorCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 908.624781 | 0.759116 | ns/op | 1024 |

| XorCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1802.717233 | 3.106054 | ns/op | 2048 |

| XorCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 3585.279127 | 6.716832 | ns/op | 4096 |

For small sizes, the fissured loop is noticeably faster, with convergence as the lengths grow.

Eventually, the bitset would get so large that doing a single pass would make more sense as it makes better use of cache, but in a BitmapContainer the length is fixed to 1024 elements, so this is immaterial.

Why is the fissured loop faster? This is because of the loop which performs the XOR operation:

for (int i = 0; i < left.length & i < right.length; i++) {

left[i] ^= right[i];

}

This loop can be autovectorised - many XORs can be computed in a single instruction.

On my laptop, running JDK11 on Ubuntu, 256 bits or 4 longs are operated on from each array at a time.

1.11% │ │││ │↗ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b892: vmovdqu 0x10(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.31% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b898: vpxor 0x10(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

0.40% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b89f: vmovdqu %ymm0,0x10(%r11,%rdx,8)

1.09% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8a6: vmovdqu 0x30(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.44% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8ac: vpxor 0x30(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

1.69% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8b3: vmovdqu %ymm0,0x30(%r11,%rdx,8)

0.42% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8ba: vmovdqu 0x50(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.31% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8c0: vpxor 0x50(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

0.77% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8c7: vmovdqu %ymm0,0x50(%r11,%rdx,8)

0.54% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8ce: vmovdqu 0x70(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.42% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8d4: vpxor 0x70(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

2.28% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8db: vmovdqu %ymm0,0x70(%r11,%rdx,8)

0.33% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8e2: vmovdqu 0x90(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.46% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8eb: vpxor 0x90(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

1.13% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8f5: vmovdqu %ymm0,0x90(%r11,%rdx,8)

0.19% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b8ff: vmovdqu 0xb0(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.36% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b908: vpxor 0xb0(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

2.38% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b912: vmovdqu %ymm0,0xb0(%r11,%rdx,8)

0.13% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b91c: vmovdqu 0xd0(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.40% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b925: vpxor 0xd0(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

1.44% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b92f: vmovdqu %ymm0,0xd0(%r11,%rdx,8)

0.15% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b939: vmovdqu 0xf0(%rdi,%rdx,8),%ymm0

0.23% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b942: vpxor 0xf0(%r11,%rdx,8),%ymm0,%ymm0

2.84% │ │││ ││ ││ 0x00007f1bc835b94c: vmovdqu %ymm0,0xf0(%r11,%rdx,8)

The other loop doesn’t get the same treatment from the compiler:

int count = 0;

for (long l : left) {

count += Long.bitCount(l);

}

return count;

Each of the popcnt instructions below operate on 64 bits each.

0.09% │││ ↗ 0x00007f3b1c35bd02: popcnt 0x28(%r11,%rbx,8),%r8

12.50% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd09: popcnt 0x20(%r11,%rbx,8),%rdi

0.02% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd10: popcnt 0x48(%r11,%rbx,8),%rdx

12.86% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd17: popcnt 0x40(%r11,%rbx,8),%r9

0.02% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd1e: popcnt 0x38(%r11,%rbx,8),%rax

0.02% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd25: popcnt 0x30(%r11,%rbx,8),%rsi

│││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd2c: popcnt 0x18(%r11,%rbx,8),%r13

7.61% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd33: popcnt 0x10(%r11,%rbx,8),%rbp

│││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd3a: add %ecx,%ebp

0.07% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd3c: add %ebp,%r13d

0.02% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd3f: add %edi,%r13d

8.25% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd42: add %r8d,%r13d

0.07% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd45: add %r13d,%esi

0.07% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd48: add %esi,%eax

7.94% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd4a: add %eax,%r9d

8.10% │││ │ 0x00007f3b1c35bd4d: add %r9d,%edx

When the loops are fused (or aren’t fissured) the XORs aren’t vectorised and only operate on 64 bits at a time.

0.31% ↗│││ 0x00007f6eac35baa0: mov 0x10(%r10,%r11,8),%rsi

2.28% ││││ 0x00007f6eac35baa5: xor 0x10(%rbx,%r11,8),%rsi

││││

││││

7.69% ││││ 0x00007f6eac35baaa: mov %rsi,0x10(%rbx,%r11,8)

││││

││││

2.06% ││││ 0x00007f6eac35baaf: popcnt %rsi,%rsi

8.92% ││││ 0x00007f6eac35bab4: add %esi,%edx

In the fused loop, the loop advances at the pace of the slowest operation.

At some point, the array would get so large that not doing two passes over the array would trump better code generation, which might be why C2 is cautious here.

Notably, the popcount operation can be vectorised and clang does so, so the fused loop written in C++ and compiled with clang would be much faster.

clang will also perform loop fission (which it calls distribution).

This is a good example of performance intuition from one language not carrying over into another.

Group By

I recently started working on Apache Pinot, which is a scalable OLAP store. In a group by query, values from one column are aggregated by values in another, and in Pinot this is performed on a block of data at a time. One of the steps in the aggregation is to copy a set of dictionary ids corresponding to the groups and to mark which groups are present in the block so they can be iterated over when aggregating the other column. The total number of groups for the entire column is known from statistics collected about the values, but not at the block level. The fused and fissured operations look like this (resetting the array would not happen for real but is necessary to make the benchmark stable):

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

public class GroupCount {

@Param({"8", "64", "128"})

int groups;

@Param({"256", "512", "1024", "2048", "4096"})

int length;

private byte[] source;

private byte[] dest;

private boolean[] presence;

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void setup() {

source = new byte[length];

dest = new byte[length];

presence = new boolean[groups];

SplittableRandom random = new SplittableRandom(42);

for (int i = 0; i < source.length; i++) {

source[i] = (byte) random.nextInt(groups);

}

}

@Benchmark

public void fused(Blackhole bh) {

int numGroups = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < source.length & i < dest.length; i++) {

dest[i] = source[i];

if (numGroups < groups && !presence[source[i]]) {

presence[source[i] & 0xFF] = true;

numGroups++;

}

}

bh.consume(presence);

Arrays.fill(presence, false);

}

@Benchmark

public void fissured(Blackhole bh) {

System.arraycopy(source, 0, dest, 0, source.length);

int numGroups = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < source.length & i < dest.length & numGroups < groups; i++) {

if (!presence[source[i]]) {

presence[source[i] & 0xFF] = true;

numGroups++;

}

}

bh.consume(presence);

Arrays.fill(presence, false);

}

}

This is a little more interesting than the other loop.

Firstly, splitting the loops makes it obvious that the copy part is a manual System.arraycopy.

The second loop can terminate whenever numGroups == groups without consuming the entire input, but in the fused loop has to carry on to ensure the entire (slow) manual array copy can take place.

Whilst fission makes the copy fast, and an obvious candidate for removal, fission allows the second loop to terminate early.

Early termination isn’t necessarily a good thing because if the number of groups is high enough for it to be likely that no single block will contain all the groups, the loop won’t exit early. Worse, with early termination, the exit condition from the loop is data dependent, which prevents aggressive unrolling, so the loop will actually be slower when it doesn’t exit early.

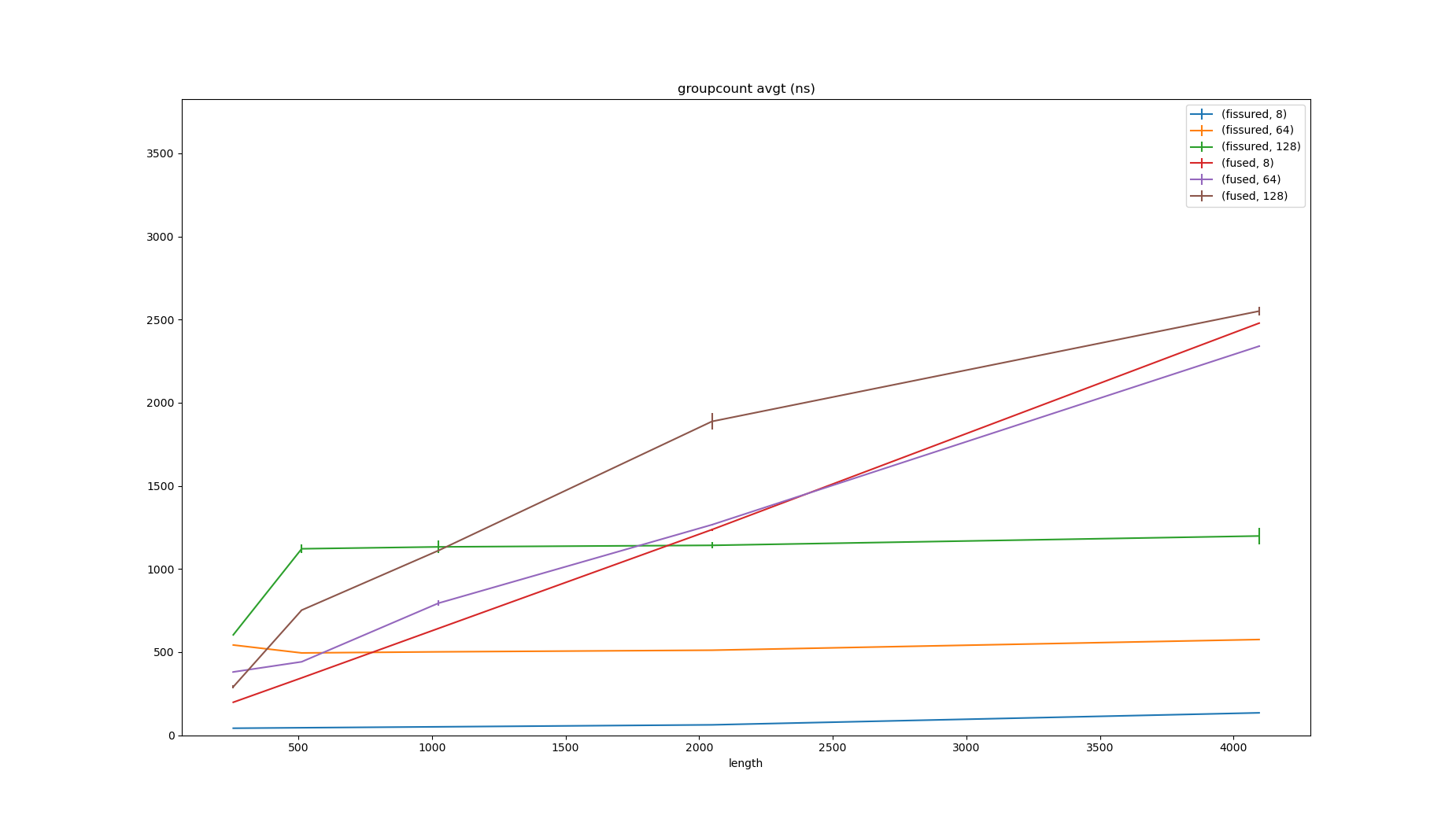

| Benchmark | Mode | Threads | Samples | Score | Score Error (99.9%) | Unit | Param: groups | Param: length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 41.606830 | 0.187490 | ns/op | 8 | 256 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 44.518117 | 0.183473 | ns/op | 8 | 512 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 50.099552 | 0.263780 | ns/op | 8 | 1024 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 61.991607 | 0.254863 | ns/op | 8 | 2048 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 134.196339 | 0.138997 | ns/op | 8 | 4096 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 542.240261 | 1.993239 | ns/op | 64 | 256 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 494.577003 | 0.331404 | ns/op | 64 | 512 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 501.147187 | 0.265733 | ns/op | 64 | 1024 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 510.997369 | 1.264461 | ns/op | 64 | 2048 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 575.261847 | 0.583042 | ns/op | 64 | 4096 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 603.379813 | 1.389718 | ns/op | 128 | 256 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1121.185683 | 26.927230 | ns/op | 128 | 512 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1132.562254 | 36.868698 | ns/op | 128 | 1024 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1141.871722 | 18.612546 | ns/op | 128 | 2048 |

| GroupCount.fissured | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1198.111175 | 49.512727 | ns/op | 128 | 4096 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 197.811972 | 0.352569 | ns/op | 8 | 256 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 344.481666 | 0.602220 | ns/op | 8 | 512 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 642.021575 | 2.235174 | ns/op | 8 | 1024 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1236.629115 | 7.446193 | ns/op | 8 | 2048 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 2478.591752 | 2.470746 | ns/op | 8 | 4096 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 380.130086 | 1.642884 | ns/op | 64 | 256 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 441.293203 | 1.776462 | ns/op | 64 | 512 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 793.848668 | 17.267290 | ns/op | 64 | 1024 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1265.961589 | 5.980144 | ns/op | 64 | 2048 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 2340.019651 | 4.249029 | ns/op | 64 | 4096 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 290.768967 | 9.365530 | ns/op | 128 | 256 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 752.002294 | 0.905900 | ns/op | 128 | 512 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1110.519415 | 1.109794 | ns/op | 128 | 1024 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 1887.382144 | 48.908744 | ns/op | 128 | 2048 |

| GroupCount.fused | avgt | 1 | 5 | 2550.872751 | 23.857060 | ns/op | 128 | 4096 |

As can be seen above, loop fission changes things a lot, and the effect of the number of groups is more pronounced in the fissured implementation.

When the ratio between length and groups is high, the fissured implementation wins (see 4096/8 134ns vs 2479ns).

When the ratio is low, the effect is less extreme but in the opposite direction (see 512/128 1121ns vs 752ns).

If you like looking at things like perfasm output to compare the counted and non–counted loop, it is here.

Given that there are statistics about the number of groups, and the block size is a small and bounded value, fission allows a data driven decision to be made for whether to attempt to exit the second loop early.